At 10:59 a.m. on Nov. 11, 1918, a German machine gun crew fired a burst of rounds at approaching Americans. One bullet struck 23-year-old Pvt. Henry Gunther in the left temple. He died instantly.

Sixty seconds later, the guns fell silent across the Western Front.

Gen. John Pershing would officially designate Gunther as the last American soldier killed in World War I. He was one of approximately 2,738 men who died that morning — casualties of the six-hour window between the armistice signing and its enforcement. He is thought to be the last soldier of any nation to die during the war.

As Americans observe Veterans Day, Gunther’s death captures both the valor of military service and the sometimes cruel outcomes of war.

A German-American Bank Clerk Goes to War

The war found Henry Gunther working behind a desk at the National Bank of Baltimore. Born June 6, 1895, he was the eldest son of George and Lina Gunther, both children of German immigrants who settled in Highlandtown, a heavily German neighborhood in East Baltimore. The family attended Sacred Heart of Jesus Roman Catholic parish, where Henry had organized and led a youth cadet program with about 85 boys.

His mother would later describe him as “the life of the house” — someone with gentle manners and a willingness to help anyone who needed it.

When Congress declared war on Germany in April 1917, German-Americans faced intense scrutiny. Some were accused of disloyalty. Others faced violence. Gunther didn’t rush to enlist, but he prepared himself for military service in 1916 by training at Plattsburg with a hospital unit.

When Congress declared war on Germany in April 1917, German-Americans faced intense scrutiny. Some were accused of disloyalty. Others faced violence. Gunther didn’t rush to enlist.

The draft called for him in September 1917. He reported to Camp Meade and was assigned to the 313th Infantry Regiment, 79th Division — a unit that would become known as “Baltimore’s Own.” His organizational skills earned him a promotion to supply sergeant, handling equipment and clothing for his company. In July 1918, he shipped to France.

A Letter That Cost Him Everything

Gunther wrote home from the trenches. He described the brutal conditions at the front — the mud, the fear, the constant artillery. He told a friend to do whatever was necessary to avoid being drafted.

Army postal censors intercepted the letter. In wartime, mail from soldiers was routinely screened for intelligence leaks and anything that might damage morale. Gunther’s letter violated both.

The punishment was immediate and severe. The Army stripped Gunther of his sergeant’s stripes and yanked him from supply duties. He was busted down to private and sent to the front lines as a rifleman just as his regiment prepared for two months of continuous combat in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

Some accounts suggest his troubles went further than military punishment. His grand-niece Carol Gunther Aikman told the History Channel that Gunther’s fiancée broke off their engagement after learning of the demotion.

However, a February 1919 Baltimore Sun article — published just months after Gunther’s death — identifies Olga Gruebl as his fiancée and describes her attending a meeting with his parents and the regiment’s chaplain. The article notes they had planned to marry on his birthday, June 6, 1918, but postponed due to the war. Gruebl never married after Gunther’s death, dying in 1964.

Whatever the truth about his personal life, the demotion devastated Gunther professionally and psychologically.

A Soldier Trying to Prove Something

Baltimore Sun reporter James M. Cain had served as a private in France during the war. Afterward, he interviewed soldiers from Gunther’s unit about the final day.

Cain would later gain fame writing noir novels, including “The Postman Always Rings Twice” and “Double Indemnity,” but in 1919, he was documenting what happened to a fellow Baltimorean.

According to Cain’s reporting, Gunther’s comrades noticed an immediate transformation. The outgoing sergeant became withdrawn and brooding. He fixated on one goal, and that was proving he wasn’t a coward or a German sympathizer.

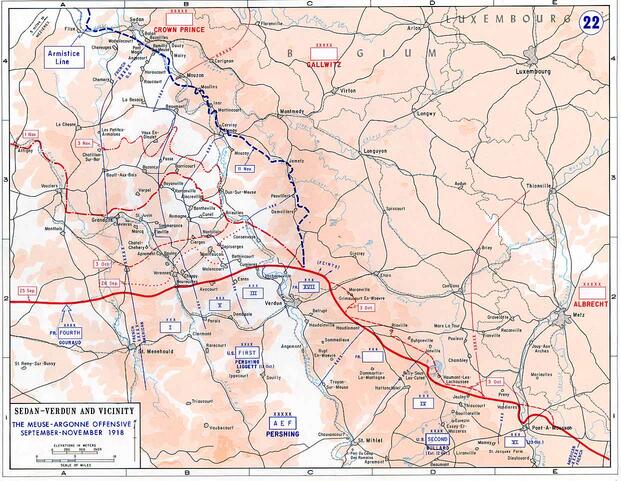

During the Meuse-Argonne Offensive that fall — a massive operation involving more than a million American troops — Gunther volunteered for increasingly dangerous assignments. When the regiment needed runners to carry messages between command posts, Gunther stepped forward. The job meant sprinting across open ground under enemy fire. German snipers specifically targeted runners.

For a full week, Gunther carried messages while bullets ripped past him. A German round hit him in the hand. He wrapped it himself and kept running. Days before Nov. 11, another bullet struck his wrist. The next morning, he reported for duty as usual.

The Six Hours That Killed Thousands

German, British, and French negotiators gathered in a railway dining car in a forest clearing north of Paris. Shortly after 5 a.m. on Nov. 11, 1918, they signed an armistice agreement.

Allied Supreme Commander Ferdinand Foch set the ceasefire for 11 a.m. — six hours away. The delay allowed time to transmit orders to remote sections of the front. But Foch also wanted the symbolic weight of ending the war at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month.

That symbolism came with a body count.

Rather than ordering troops to hold positions and wait, Allied commanders across the front sent their men forward. Some generals wanted to capture one more town before the armistice took effect. Artillery batteries fired off whatever shells they could to avoid hauling them away.

Historian Joseph Persico documented in “Eleventh Month, Eleventh Day, Eleventh Hour” that approximately 2,738 soldiers died on the Western Front that final morning — more than 11,000 total casualties when including wounded and missing.

A runner reached the 313th Regiment at 10:44 a.m., informing the command staff of the impending armistice.

Brig. Gen. William Nicholson, commanding the regiment, issued orders to his troops. There would be “absolutely no let-up” until exactly 11 a.m. Keep fighting for 16 more minutes.

Sixteen Minutes Left to Live

Gunther’s squad was moving through the village of Chaumont-devant-Damvillers in Lorraine when they spotted German positions ahead — two machine gun crews manning a roadblock.

The German soldiers knew the war was ending. They received word to hold their positions but avoid needless killing in the final minutes. When American troops appeared through the morning fog, the Germans fired warning shots high over their heads.

Gunther hit the ground as rounds cracked through the air. Then he did something nobody expected. He started crawling forward through the mud toward the German machine guns.

His fellow Americans screamed at him to stop. The German crews stood up from behind their weapons, waving their arms frantically. They shouted in broken English for the American soldier to go back. The war was nearly over. There was no reason for anyone to die.

Gunther either couldn’t hear them or chose not to listen. He climbed to his feet, fixed his bayonet to his rifle, and charged directly at the machine gun position. He was given an order, and he was going to see it done.

The Germans continued screaming for him to stop, but as Gunther closed in and raised his rifle, they had no choice. A five-round burst cut Gunther down; one bullet struck him in the head, the rest tore into several letters he had received from Olga and his parents. The time was 10:59 a.m.

Witnesses later reported that the artillery barrages across the Western Front seemed to stop at the precise moment Gunther’s body fell.

The German machine gunners who killed Gunther immediately grabbed a stretcher. They placed his body on it and carried him across no man’s land back to American lines. They explained what had happened.

The American and German soldiers present, having survived the war, shook hands and parted ways.

The regiment’s Catholic chaplain, Lt. Rev. George F. Jonaitis, helped dig Gunther’s grave where he fell. Jonaitis conducted the burial service, laying Gunther to rest in French soil as WWI came to an end.

Henry Gunther: Redeemed in Death

The following day, Gen. Pershing issued his “Order of the Day” announcing the end of hostilities. In that official statement, Pershing specifically identified Henry Gunther as the last American soldier killed in World War I.

Whatever redemption Gunther sought, he found it. The Army posthumously restored him to the rank of sergeant. He received the Distinguished Service Cross along with a divisional citation for gallantry in action — honors he desperately sought in life but received only after death.

Three months later, in February 1919, Lt. Jonaitis traveled to Baltimore to tell the family about Henry’s final moments. George and Lina Gunther, as well as Olga Gruebl listened. Lina broke down as the chaplain described her son’s death. The chaplain delivered Henry’s final letters to Olga.

Henry’s mother told the chaplain that her son had been “one of the best boys that ever lived” and had never given her a moment’s worry. She wanted his body brought home. If necessary, she said, she would travel to France herself to retrieve it.

In 1923, the Army exhumed Gunther’s body from a military cemetery in France and returned him to Baltimore. He was buried at Most Holy Redeemer Cemetery. His family noted the cemetery’s name seemed grimly fitting — Gunther had died trying to redeem himself.

His grave marker reads: “Highly decorated for exceptional bravery and heroic action that resulted in his death one minute before the armistice.”

Nearly nine decades after his death, on Nov. 11, 2008, the French government dedicated a memorial near the spot where Gunther fell in Chaumont-devant-Damvillers. Two years later, the German Society of Maryland unveiled a memorial plaque at his Baltimore grave. The ceremony was scheduled for 10:59 a.m.

Why We Remember Veterans on Nov. 11

The moment Henry Gunther fell became the moment that defines Veterans Day. President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed the first Armistice Day in November 1919, honoring those who died in World War I. Congress made Nov. 11 a federal holiday in 1938.

After World War II and Korea required millions more Americans to serve, Congress broadened the holiday’s scope. In 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed legislation renaming it Veterans Day — expanding recognition beyond WWI to honor all who have worn the uniform.

Congress kept the observance on Nov. 11 to preserve what that date represents: the exact moment when the guns fell silent at 11 a.m. on Nov. 11, 1918. Gunther was the last of millions to die during WWI, while over 300 other Americans died in the hours before his death that day.

Gunther’s death one minute before that silence captures why the day matters. His story — a soldier who died seeking redemption in the final moments of WWI — reflects the cost of service that Veterans Day asks Americans to remember.

Every Nov. 11, Americans honor service members like Gunther who gave everything, as well as veterans of all branches and eras, through peace and war.

Story Continues

Read the full article here