Colonel Paul Freeman’s regiment was exposed and exhausted. Chinese forces were massing nearby. On Feb. 13, 1951, Lieutenant General Edward Almond, X Corps commander, authorized a withdrawal 15 miles south.

Lieutenant General Matthew Ridgway overruled Almond.

The Eighth Army commander reversed the order after meeting General Douglas MacArthur, agreeing that the communists had to be stopped. Almond favored caution after two divisions were mauled at Hoengsong. The ever-aggressive Ridgway saw an opportunity. The Chinese had overextended their supply lines. One decisive blow could shatter them and stop their devastating advance down the Korean peninsula.

Ridgway directed Almond to launch a relief effort if Freeman was cut off. His orders to Freeman were to hold at all costs.

A Strategic Crossroads

Chipyong-ni sat 40 miles east of Seoul, straddling several vital roads through the Han River Valley. If it fell, the entire Eighth Army front could collapse. The 23rd RCT reached the village on Feb. 3 following a brutal victory at the Twin Tunnels, where Freeman’s regiment had mauled three Chinese regiments. The unit was operating at 75 percent strength.

Freeman commanded 4,500 men, including 2,500 front-line infantrymen. Attached units included the 1st Ranger Company, 37th Field Artillery Battalion, elements of the 503rd Field Artillery Battalion, Sherman tanks, antiaircraft guns, and combat engineers from various units.

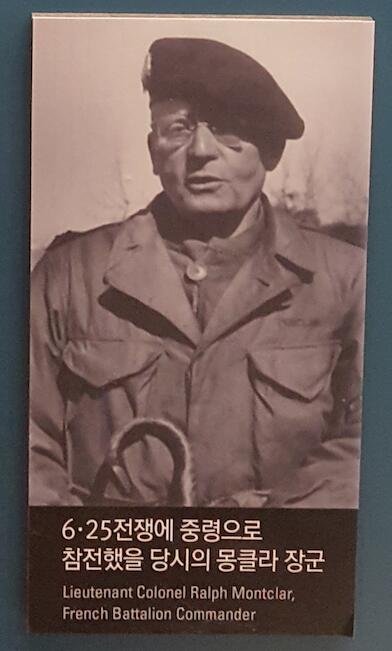

One attachment was the French Battalion under Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Monclar. Born Raoul Magrin-Vernerey, the 58-year-old had voluntarily demoted himself from three-star general to lieutenant colonel to lead 800 Frenchmen in Korea. Wounded seven times in World War I, he had led Foreign Legion troops in Morocco and commanded Free French forces in World War II. On the eve of retirement, Monclar chose to go to war again.

He wore a monocle, carried a cane for his limp, and commanded respect from his men. His battalion included hardened Legionnaires and 180 South Korean soldiers.

Freeman’s battalion commanders were Lieutenant Colonel George Russell (1st Battalion), Lieutenant Colonel James Edwards (2nd Battalion), and Lieutenant Colonel Charles Kane (3rd Battalion).

The Tactical Situation

Freeman faced a horrendous situation. Eight hills surrounded the village, creating a 12-mile ridgeline his depleted force couldn’t man. He concentrated his troops in a tight defensive ring on the low ground.

Chinese forces lacked air superiority and long-range artillery. A compressed perimeter would prevent enemy infiltration while maximizing overlapping fire.

Freeman positioned Russell’s 1st Battalion in the north, Kane’s 3rd Battalion in the east, and Edwards’ 2nd Battalion in the south. Monclar’s French Battalion held the west. Company B and the Rangers remained in reserve.

For 10 days, the troops dug in, registered their artillery, sent out patrols, and coordinated air support.

Ridgway’s goal in refusing to withdraw was to transform Chipyong-ni into a killing ground. He knew Chinese commanders couldn’t resist a surrounded UN regiment and would throw in everything they had to destroy it.

With enough firepower and air support, the encircled troops could inflict massive casualties and possibly disrupt the entire Chinese offensive. If not, they would be destroyed.

The Chinese went for it. Following their assault on X Corps at Hoengsong on Feb. 11, elements of the 39th Army and divisions from the 40th and 42nd Armies converged on the village. Chinese intelligence estimated only 1,000 UN defenders held Chipyong-ni.

The Battle Begins

Both main roads were cut by enemy troops on the afternoon of Feb. 13. The 23rd RCT was isolated 20 miles beyond friendly lines. Freeman called his commanders together.

“We are going to stay here and fight it out,” Freeman told his officers.

“When Col. Freeman said at Chipyong, ‘We’re surrounded, but we’ll stay here and fight it out,’ we supported him with enthusiasm,” Captain Bickford Sawyer of Company E later recalled. “There was never a doubt in our minds. We knew we were going to succeed.”

The Chinese began their assault at 10 p.m. Mortar and artillery fire hammered the UN positions. Temperatures dropped near freezing. Chinese bugles and whistles pierced the air around the village.

Infantry wave attacks struck Russell’s 1st Battalion first. The battle quickly spread to Edwards’ 2nd Battalion and Monclar’s French Battalion. Only Kane’s 3rd Battalion remained initially unengaged.

The French Battalion fought with ferocity that stunned both the Americans and the Chinese

As the Chinese forces attacked the French sector, they overran a section of the 3rd Company’s line. Lieutenant Ange Nicolai commanded a rearguard that bought time for a withdrawal. Nicolai was wounded and left behind in the chaos.

Monclar’s troops launched an immediate counterattack unlike anything the Chinese had encountered thus far. The French blasted their own sirens and bugles, mimicking the Chinese assault signals.

The charging Chinese forces slowed, confused by what was happening. Then the French fixed bayonets.

The French soldiers leapt from their positions and charged howling across open ground right into the Chinese wave. The Legionnaires were trained in close combat, using blades, rifle butts and their bare-hands to kill the enemy troops.

The unexpected assault shattered Chinese cohesion. The enemy troops broke and fled back into the hills. The French retook their positions and held them for the rest of the battle. It became the most celebrated action of the French Battalion’s Korean War service.

Company G in Edwards’ sector came under attack around the same time. Lieutenant Thomas Heath commanded his men through the desperate fighting. A Sherman tank provided support as the position nearly collapsed.

Hundreds of Chinese infantry ran head-first into the wall of American firepower as flares, artillery blasts, and the muzzle flashes of hundreds of rifles and machine-guns lit up the night.

The occasional Chinese soldier that reached the American fighting positions soon found themselves in hand-to-hand combat.

Heath’s men held the line.

Valentine’s Day

At dawn on Feb. 14, the Chinese withdrew to consolidate and avoid possible American air strikes. Fresh snow dusted hundreds of bodies across the battlefield. The defenders had suffered approximately 100 casualties. Freeman took shrapnel in his leg and limped through the perimeter while encouraging his troops.

The men got to work repairing their defenses and preparing their weapons for the next attack.

Overcast skies hampered UN air support and emboldened the Chinese. The communists could continue massing near UN lines without the fear of fighter-bombers. Air Force, Navy, and Marine pilots waited on station for any breaks in the clouds. C-119 Flying Boxcars made 24 ammunition airdrops as they could, but close air support remained impossible in such weather.

That afternoon, Ridgway flew in by helicopter. He toured the garrison, promised relief was coming, and asked them to hold for just one more night.

The men knew the Chinese were going to attack soon. They needed a miracle to survive another night.

The Desperate Hours

The Chinese renewed their attacks after darkness set in on Feb. 14. Edwards’ 2nd Battalion faced the heaviest pressure.

Heath rallied artillerymen from Battery B, 503rd Field Artillery Battalion, to reinforce his line. When some hesitated under fire, Heath grabbed them by their uniforms.

“Goddammit, get back up on that hill!” Heath yelled. “You’ll die down here anyway. You might as well go up on the hill and die there.”

Captain John Elledge, an artillery liaison, heard Heath’s shouting. He raced to the firing positions, grabbed about a dozen artillerymen, and forced them up to the line. Elledge carried a .30-caliber machine gun. He met the Chinese face to face and killed two in hand-to-hand combat before a grenade blast mauled his left arm.

Companies E and G defending Hill 397 detonated fougasse drums filled with gasoline and oil. As the attackers closed in, the defenders detonated grenades beneath them, spraying Chinese troops with burning liquid.

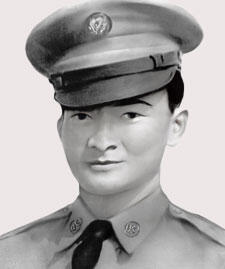

In the midst of the battle, Sergeant First Class William Sitman was leading his troops from Company M. Chinese grenades detonated around them, knocking out one of their machine-gun crews.

Sitman and his men reoccupied the position, but then he saw another grenade land among his men. He threw himself on it without hesitation. The explosion killed Sitman instantly but saved at least five soldiers. He received the Medal of Honor posthumously.

Just before 4 a.m., Lieutenant Robert Curtis led a composite force of Rangers, Company F, and Company G men in a counterattack. Captain John Ramsburg joined them but was wounded. Heath was seriously wounded as well. Most platoon officers were killed.

The surviving Americans and masses of Chinese troops were engaged in fierce close-combat.

Three tanks suddenly unleashed fire on the hilltops, assuming they were blasting the enemy, not realizing Americans were in the mix. Only Curtis’ screaming across the battlefield halted the friendly fire. A Chinese counterattack overwhelmed the exhausted men.

Curtis and the survivors fell back down the hill and formed a last-ditch ring of 15 men in front of the 155mm howitzers.

They held the line against overwhelming waves of Chinese assaults.

Air Support Arrives

By the morning of Feb. 15, Freeman’s perimeter was collapsing. Ammunition was critically low. The southern hills remained in Chinese hands and casualties were mounting. His perimeter was shrinking under relentless enemy assaults.

Private Bruno Orig had been on a wire-laying mission when he returned to find his Company G position under enemy attack. He administered first aid to the wounded sprawled along the ground. As Chinese fire flew over his head, Orig began evacuating the wounded.

As he returned to the line again, he realized most of a machine-gun crew had been wounded. Orig manned the weapon himself. He unleashed heavy fire into the attacking waves of Chinese troops, which allowed another platoon to withdraw.

When American forces retook the ground soon after, they found Orig dead behind his machine gun with piles of enemy soldiers dead in front of the weapon. Orig initially received the Distinguished Service Cross, which was upgraded to the Medal of Honor in January 2025.

Suddenly, the weather cleared up.

Patches of blue sky were now visible to the troops on the ground, who knew support was likely on the way. Air Force jets and Marine Corsairs dove through the clouds. The pilots risked flying blind through cloudy mountain valleys to reach Chipyong-ni.

The fighter-bombers dropped 500-pound bombs into Chinese positions and raked formations with machine guns and rockets. Napalm tumbled into the hills where Chinese troops massed for another assault. Navy pilots from aircraft carriers joined the strikes.

The intensity of close air support turned the tide of the entire engagement. Chinese troops, caught in the open, broke and scattered into the wilderness.

The Relief Column

As ammunition dwindled on Feb. 15, relief finally arrived. Colonel Marcel Crombez of the 5th Cavalry Regiment organized an armored task force to break through to the encircled men.

Task Force Crombez consisted of 23 tanks and 160 men from Company L mounted on the armor. Lieutenant Colonel Edgar Treacy, commander of the 3rd Battalion, 5th Cavalry, protested Crombez’s plan to send infantry riding in exposed through heavy fire. When Crombez refused to change his tactics, Treacy insisted on accompanying the mission alongside the infantrymen. Crombez denied him permission.

Treacy went anyway, hitching a ride on the sixth tank.

The column departed at 3 p.m. and immediately came under fire. Chinese roadblocks and troops on the ridges hammered the exposed infantry. Tank commanders buttoned their hatches. The men on top had no protection.

Communications broke down. Some tanks moved forward while infantry were still dismounted and clearing enemy positions. Chinese troops swarmed the road, cutting off soldiers from the column.

Captain John Barrett watched his company disintegrate. Men fell from tanks under machine-gun fire. Others jumped to take cover and were left behind. The engineers assigned to clear mines were cut off entirely. Chinese troops overran any isolated groups in the ditches.

The lead tank, commanded by Lieutenant Lawrence DeSchweinitz, blasted through the final roadblock. At 5:10 p.m., the tanks rolled into the perimeter. Barrett frantically counted his men. Only 23 riflemen had made it. More than 130 soldiers were dead, wounded, captured, or stranded along the route.

Treacy was among the captured. Chinese troops stopped a truck following the column and took the men prisoner, including the wounded battalion commander. Treacy would die as a POW three months later from malnutrition.

His family petitioned for the Medal of Honor. The award was never granted.

But the tanks were vital to the defense. The Chinese had already suffered heavy while charging the perimeter. The close air support had decimated their ranks. Now the UN troops had extra fire support on the ground.

The Chinese also discovered the garrison actually contained more than 6,000 troops rather than the estimated 1,000. The Chinese knew there was no point in launching any further assaults. They began withdrawing from the battlefield.

Freeman was evacuated by helicopter on Feb. 15 for the wounds he sustained. Lieutenant Colonel John Chiles assumed command. Chiles went on to praise the French Battalion for their heroics during the battle.

“The French are some of the fightingest men I have ever seen,” Chiles said. “When they attack a position, they carry it. When they hold a position, they hold it.”

The Turning Point

UN casualties totaled 52 killed, 259 wounded, and 42 missing. Chinese losses reached up to 5,000 killed and wounded. The 23rd RCT and attached units received the Presidential Unit Citation. Freeman earned the Distinguished Service Cross for his heroic leadership.

Chipyong-ni marked the first clear Chinese tactical defeat since entering the war. The psychological impact exceeded the military results. For three months, UN forces had retreated whenever the Chinese attacked in strength. The UN forces had retreated ever since Chosin, against a seemingly invincible enemy army.

Freeman’s stand shattered the communists. Within a week, Ridgway launched Operation Killer to inflict maximum casualties on withdrawing Chinese forces. UN troops advanced aggressively for the first time since November. They recaptured Seoul on March 14. By the month’s end, UN forces had pushed across the 38th parallel again.

Chinese commanders never again attempted massive encirclement operations against dug-in UN positions. They learned that American firepower, particularly air support and artillery, could devastate massed infantry attacks. The strategic initiative shifted back to UN forces.

Ridgway addressed Congress in May 1952 and discussed the successful battle.

“Twice isolated far in advance of the general battle line, twice completely surrounded in near-zero weather, they repelled repeated assaults by day and night by vastly superior numbers of Chinese infantry,” Ridgway said. “I want to record here my conviction that these American fighting men and their French comrades in arms measured up in every way to the battle conduct of the finest troops America or France has produced throughout their national existence.”

Military historians dubbed the Battle of Chipyong-ni the “Gettysburg” of Korea. Like that 1863 battle which halted the Confederate advance, this engagement stopped Chinese momentum. Chinese forces never again threatened to drive UN troops from the peninsula.

Read the full article here