North Vietnamese negotiators walked out of peace talks in Paris on Dec. 13, 1972. They had just rejected American proposals and refused to set a date to resume discussions. Five days later, American B-52 bombers struck Hanoi in the most intensive bombing campaign in military history.

Eleven days after that, North Vietnam requested new negotiations. Operation Linebacker II brought the communist government back to the negotiation table and led directly to the Paris Peace Accords signed Jan. 27, 1973.

The bombing campaign sparked international condemnation and remains controversial five decades later. Critics called it barbaric. Supporters argued it achieved its objective. The historical record shows the operation succeeded as a coercive action but created an agreement both sides immediately violated.

The accord ended American combat involvement in Vietnam but left South Vietnam defending itself against North Vietnamese forces that remained in the country.

The Road to Linebacker II

American involvement in Vietnam’s air war began with Operation Rolling Thunder in March 1965. President Lyndon Johnson authorized sustained bombing of North Vietnam to force Hanoi to stop supporting communist insurgents in South Vietnam. The campaign lasted three years and dropped 864,000 tons of bombs on North Vietnamese targets.

Rolling Thunder failed to achieve its objectives. Political restrictions prevented strikes on many valuable military targets including airfields near Hanoi, port facilities at Haiphong, and power plants in populated areas. Johnson worried that destroying these targets might provoke Chinese intervention.

Between March 1965 and November 1968, American forces flew more than 300,000 attack sorties but never broke North Vietnam’s will to fight.

A 1966 Defense Department analysis concluded that despite significant physical damage, North Vietnam continued increasing its support for the war in South Vietnam. Soviet and Chinese aid flowing into North Vietnam exceeded bomb damage costs by five to one.

Hanoi mobilized its population for war production and reconstruction. The campaign managed to divert 70,000 North Vietnamese troops to air defense and employed 320,000 workers in repair efforts, but it never threatened the regime’s survival.

Johnson halted Rolling Thunder on Oct. 31, 1968, hoping to pursue further peace negotiations and get American troops out of the conflict. Those talks stalled for three years. North Vietnam remained unwilling to accept any settlement that left South Vietnam’s government in power.

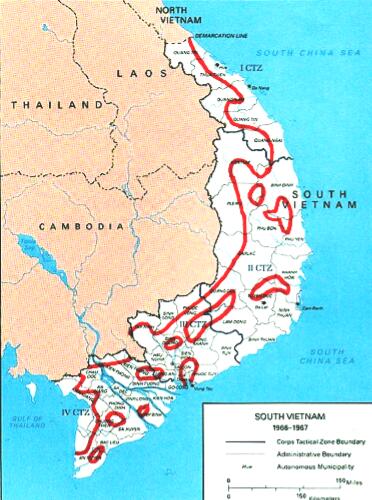

During that time, American and communist troops remained locked in violent ground battles that raged from the DMZ to the Mekong Delta and even into Laos and Cambodia. American bombing missions, including Operation Barrel Roll and Operation Menu, shifted focus to attacking targets in neighboring countries and VC positions in the South.

The Easter Offensive Changes Everything

By 1972, most American ground troops had been withdrawn as the combat mission was handed over to the ARVN. On March 30, North Vietnam launched its largest offensive of the war. Three divisions with tanks and artillery crossed the demilitarized zone while other forces attacked from Laos.

The Easter Offensive aimed to capture South Vietnamese territory and strengthen Hanoi’s negotiating position before American troop withdrawals were completed. President Richard Nixon responded with Operation Freedom Train, which evolved into Linebacker I in May.

Unlike Rolling Thunder, Linebacker removed most targeting restrictions. American commanders chose targets and tactics without constant political oversight. Airstrikes hit power plants, shipyards, petroleum facilities, and transportation networks throughout North Vietnam, but caused thousands of civilian casualties.

The campaign also included dropping mines into North Vietnamese ports. On May 9, Navy aircraft dropped mines in Haiphong harbor, effectively closing it to Soviet supply ships. This interdiction proved more effective than Rolling Thunder’s attempts to bomb supply lines.

Linebacker I lasted from May 9 to Oct. 23, 1972. Air Force and Navy aircraft flew thousands of sorties and dropped more than 155,000 tons of bombs. Precision-guided munitions destroyed targets that survived Rolling Thunder. American pilots knocked down the Thanh Hoa Bridge on May 13 using laser-guided bombs after years of failed attempts with conventional weapons.

The offensive in South Vietnam stalled by summer. North Vietnamese forces suffered heavy casualties and ran low on supplies. In August, Hanoi indicated a willingness to negotiate peace. By October, American and North Vietnamese negotiators reached a tentative agreement on most major issues.

Peace Within Reach

National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger and North Vietnamese politburo member Le Duc Tho met secretly in Paris throughout 1972. By October, they had worked out an agreement. North Vietnam dropped its demand that South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu be removed from power. The United States begrudgingly accepted that North Vietnamese troops could remain in South Vietnam after a ceasefire.

Kissinger announced on Oct. 26 that “peace is at hand.” Nixon had already ordered the halt of bombing above the 20th parallel on Oct. 23.

South Vietnam’s government outright rejected the agreement. Thieu refused to accept any terms that allowed North Vietnamese forces to remain in his country. He demanded changes. American negotiators returned to Paris with a list of 69 modifications.

North Vietnamese negotiators viewed the new demands as another American betrayal. They believed Washington had agreed to terms in October but now sought to change them under pressure from Saigon. Talks deteriorated through late November and December. On Dec. 13, North Vietnamese representatives refused to negotiate further and walked out.

The Christmas Bombing

Nixon faced a political crisis. Kissinger’s “peace is at hand” statement had raised public expectations. The new Congress would convene Jan. 3, and Democrats opposed to the war might legislate an end to American involvement on unfavorable terms. Nixon needed a settlement before his inauguration on Jan. 20.

On Dec. 14, Nixon gave Hanoi a 72-hour ultimatum to return to the negotiations. North Vietnam ignored it. On Dec. 18, Operation Linebacker II began.

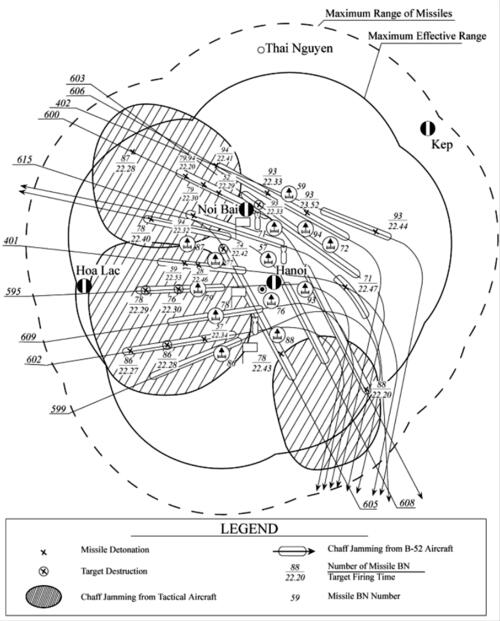

The campaign concentrated bombing on Hanoi and Haiphong. B-52s flew from bases in Guam and Thailand. Fighter-bombers provided support. Targets included transportation facilities, rail yards, power plants, communication centers, air defense sites, and military storage areas.

The first three nights of attacks followed rigid tactical patterns. North Vietnamese surface-to-air missile batteries exploited these patterns and shot down several B-52s. American commanders adjusted their tactics on the fourth night, varying approach routes and altitudes. Losses dropped significantly.

Nixon suspended bombing for 36 hours over Christmas. When operations resumed on Dec. 26, American forces struck with an even greater intensity. B-52s flew multiple waves against any remaining targets. By Dec. 29, North Vietnam had exhausted most of its surface-to-air missile inventory.

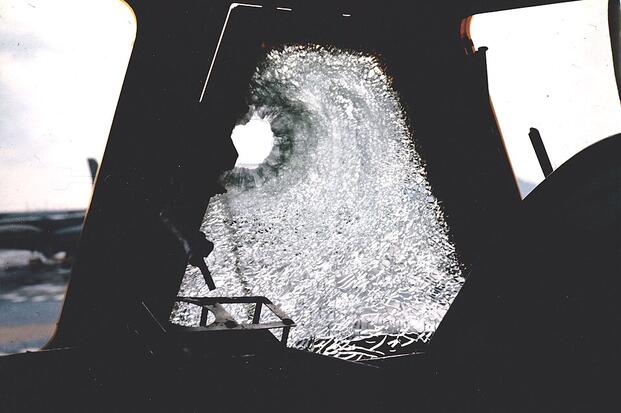

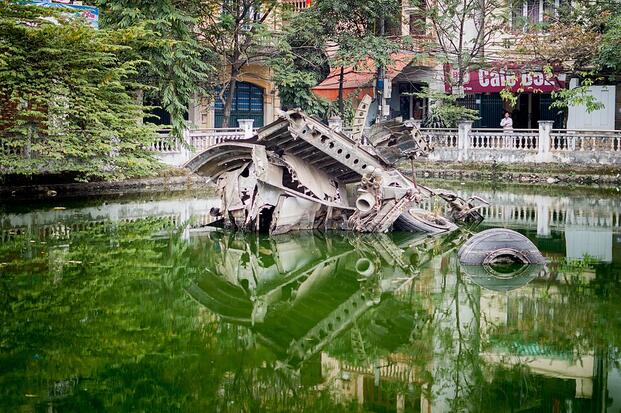

The campaign flew 729 B-52 sorties and more than 1,000 fighter-bomber sorties. American forces dropped over 20,000 tons of ordnance. The United States lost 15 B-52s and 11 other aircraft. North Vietnamese sources reported at least 1,600 civilian deaths in Hanoi and Haiphong.

The international reaction was harsh. Critics from the Soviet Union to even NATO allies compared the bombing to Nazi attacks during World War II. American newspapers used words like “genocide” and “barbarism.” But North Vietnam sent a message on Dec. 26 indicating their willingness to resume the peace talks.

Nixon ordered all bombing to cease on Dec. 30. Negotiations resumed in Paris on Jan. 8, 1973.

The Paris Peace Accords

American and North Vietnamese representatives reached an agreement quickly. They signed the Paris Peace Accords on Jan. 27. The terms closely resembled the October agreement that South Vietnam had rejected.

The accord established an immediate ceasefire. The United States agreed to withdraw all troops and advisors within 60 days. North Vietnam agreed to release American prisoners of war for the return of captured communist troops. Both sides pledged to withdraw forces from Laos and Cambodia.

The settlement allowed North Vietnamese troops to remain in South Vietnam. It created a National Council of Reconciliation and Concord to oversee the political arrangements. An international commission would supervise compliance from sides.

Nixon privately assured Thieu that America would respond with airpower if North Vietnam violated the agreement. He also promised continued military aid. Under this promise, Thieu accepted the treaty.

Some 591 American prisoners returned home in Operation Homecoming between February and April 1973. The last American combat troops left South Vietnam on March 29. The United States maintained a small presence of advisers and embassy guards.

An Agreement in Name Only

Both sides violated the Paris Peace Accords immediately. Fighting resumed within weeks of the ceasefire. North Vietnam continued infiltrating troops and supplies into South Vietnam. South Vietnamese forces attempted to recapture territory lost during the Easter Offensive.

By March 1973, full-scale war had resumed only weeks after the peace treaty was signed. Thieu officially announced in January 1974 that the agreement was no longer in effect. More than 25,000 South Vietnamese soldiers became casualties during the supposed ceasefire period.

Nixon had promised to punish violations with renewed bombing, but Watergate destroyed his political power. Congress moved to prevent any resumption of combat operations. In August 1973, lawmakers prohibited further American military action in Indochina without congressional approval. With that, South Vietnam was on its own.

North Vietnam interpreted American inaction as proof that Nixon’s threats were empty. Hanoi issued Resolution 21 in late 1973, calling for strategic raids to test South Vietnamese and American resolve. When these attacks produced no American response, North Vietnam began planning a final offensive.

The Fall of South Vietnam

South Vietnam depended on American airpower and military aid to survive. When both disappeared, the regime’s days were numbered. Congress reduced military assistance in 1974. By early 1975, South Vietnamese forces faced critical ammunition and fuel shortages.

North Vietnam launched its final offensive in March 1975. South Vietnamese defenses collapsed and communist tanks blitzed into Saigon. The city fell on April 30. The two countries unified under communist control in 1976.

The Paris Peace Accords accomplished the primary American objective of ending direct military involvement in Vietnam. The agreement gave Nixon his “peace with honor.” It allowed the United States to withdraw forces and recover prisoners while maintaining the fiction that South Vietnam remained independent and the war had been “won.”

On paper, the settlement ended the Vietnam War in something resembling a draw. Both sides agreed to a ceasefire. Both sides kept forces in place. The final political outcome would be determined through negotiations rather than military victory.

In reality, all parties understood the agreement was temporary. North Vietnam never abandoned its goal of reunifying Vietnam under communist control. South Vietnam knew communist troops would continue their offensives. The accord simply removed American forces from the region and allowed them to save face after a devasting and unpopular war. Once American troops left and Congress blocked renewed intervention, North Vietnam faced only weakened South Vietnamese resistance.

The Legacy of Linebacker II

Linebacker II remains controversial. Critics continue to argue the bombing accomplished nothing that couldn’t have been achieved through continued negotiations. They point out that the January agreement matched the original October terms. They emphasize civilian casualties and international condemnation.

Supporters contend the bombing proved necessary to convince Hanoi that continued delay would prove costly. They note North Vietnam requested talks within days of the bombing. They argue the campaign demonstrated American resolve and assured Thieu that Washington would support South Vietnam.

The broader question remains whether American bombing ever could have succeeded in Vietnam. Rolling Thunder failed despite three years of sustained attacks. Linebacker I achieved tactical success but required favorable battlefield conditions during North Vietnam’s offensive. Linebacker II forced peace negotiations but led to an agreement neither side honored.

American airpower inflicted massive damage on North Vietnam throughout the war. However, it never broke Hanoi’s determination to unify Vietnam under communist rule. North Vietnam proved willing to suffer enormous losses to achieve its objectives.

That reality was clear to many at the time. Kissinger and Le Duc Tho shared the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize. Tho declined to accept it, claiming that the agreement was being violated by ARVN troops. Kissinger accepted but later offered to return the award after South Vietnam’s collapse.

Regardless of the outcome, the accords were a political necessity for the United States to exit the Vietnam conflict. Linebacker II brought North Vietnam to the table, but it could not create a lasting peace. The war’s final outcome was decided on South Vietnamese battlefields two years after American forces withdrew.

Story Continues

Read the full article here