Every morning over breakfast in early 1942, the infamous German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel received a classified intelligence briefing. The reports detailed British troop positions, supply routes, convoy schedules and operational plans across North Africa — intelligence so precise that Rommel called it “die gute Quelle,” the good source.

His source wasn’t a spy within British command. It was an American embedded with the British.

Col. Bonner Fellers, the U.S. military attaché in Cairo, had no idea his detailed reports to Washington were feeding intel to the Desert Fox. Italian intelligence had stolen the codes Fellers used to transmit his dispatches, and for six critical months, every assessment he sent became a hindrance for Allied forces.

The Italian Secret Service Breaks Into the American Embassy

In September 1941, three months before Pearl Harbor, Italian spies executed one of World War II’s most successful intelligence operations. An American embassy worker in Rome, Loris Gherardi, stole a set of keys and passed them to Italy’s Servizio Informazioni Militare, Italy’s wartime intelligence agency.

Gen. Cesare Amè, head of Italian military intelligence, later recalled the operation wasn’t difficult: “All I had to do was reach for the American Embassy key from my office wall.”

Under the cover of darkness, Italian agents entered the embassy, photographed every page of the Black Code — the cipher system American diplomats and attachés used worldwide — and returned the codebook within two hours. The Americans never knew what happened.

An American in Cairo and His Intelligence Leaks

When Fellers arrived in Egypt in October 1940, British commanders saw an opportunity. Desperate for American support, they gave the West Point graduate unparalleled access to information about their Mediterranean operations, including detailed briefings on troop movements, supply convoys and battle plans. The plan was to prove the success of British efforts in the region to inspire the American public to enter the war.

However, Fellers voiced concerns about the Black Code’s security, noting the system was old, but his superiors ignored his objections. He sent everything he learned from the British back to Washington, where President Franklin Roosevelt, the Joint Chiefs of Staff and intelligence chiefs read his assessments.

So did the Axis.

Within eight hours of his first transmission, Italian cryptographers decoded Fellers’ reports. They passed the information to Italian commanders in Rome, who then transmitted the data to Rommel and Axis forces in North Africa. From December 1941 through June 1942, Rommel received these detailed intelligence reports on British strengths, positions, losses, reinforcements, supply situations and plans.

The Germans nicknamed Fellers “the little fellers,” a play on his name. Rommel simply called him the good source.

Axis Successes and the Cost in Blood

The intelligence leak helped ensure some of Rommel’s greatest victories.

In January 1942, Fellers reported that 270 aircraft and antiaircraft guns were being withdrawn from North Africa to reinforce British forces in the Far East. With this knowledge, Rommel launched a counteroffensive that recaptured Benghazi and pushed the British back to Gazala.

The leaked intelligence proved most devastating during Operation Julius in June 1942, when the British attempted to resupply Malta with two simultaneous convoys. Intelligence about both operations had been unwittingly revealed to the Axis by Fellers’ reports.

On June 11, Fellers sent report No. 11119 detailing the entire operation: convoy routes, escort strengths, timing and planned commando raids on Axis airfields to support the convoys. Berlin and Rome moved to counter every element of the British plan.

The commandos and paratroopers came under intense fire as garrisons at the Axis airfields were put on alert. No Axis aircraft were destroyed.

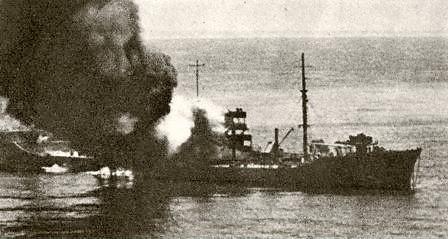

Operation Vigorous sailed from Alexandria with 11 merchant ships. After four days of attacks by aircraft, torpedo boats and submarines, with the Italian battle fleet closing in, the convoy turned back. One cruiser and three destroyers were lost, along with two merchant vessels.

Operation Harpoon fared only slightly better. Of six merchant ships that left Gibraltar, only two reached Malta after Italian cruisers and aircraft decimated the convoy. The destroyer HMS Bedouin and three merchantmen were sunk. While the minuscule delivery of oil and supplies helped ensure Malta’s survival, the cost in lives and material was staggering.

While the convoys were being mauled, Rommel launched his Gazala offensive on May 26, considered the greatest victory of his career. By June 21, Tobruk fell, with 32,000 Commonwealth troops captured — the largest British surrender after Singapore.

Seeing the British reeling from these setbacks, Rommel launched his forces deep into the Egyptian desert.

The Intelligence Leak Gets Plugged

British intelligence detected suspicious Axis signals as early as January 1942, including one citing “a source in Egypt.” Whenever an air patrol left an airfield or a convoy sortied into the Mediterranean, Axis planes and ships seemed to appear. The British quickly deduced that the source in Egypt had access to highly sensitive information that no ordinary spy would be able to decode. In June 1942, the British informed Washington that their secret codes had been compromised.

On June 29, Fellers switched to a new code system, ending the leak. The intelligence advantage during the North African Campaign shifted when British codebreakers at Bletchley Park exposed Axis communications while cutting off Rommel’s source. Almost overnight, Rommel became the one who was unable to submit secure intelligence reports while losing his greatest advantage over the British.

Fellers was silently removed from the region after the scandal, though he was promoted to Brigadier General and even awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his reporting in Egypt.

Without the good source, Rommel’s advance stalled at El Alamein. By November, the Afrika Korps was in full retreat as the Allies closed in on both sides of North Africa.

The Worst Intelligence Leak of WWII

Fellers never faced any official blame for the disaster. When he returned to Washington in July 1942, Roosevelt even invited him to the White House.

“Consistent with his previous reporting through 1942, Fellers argued for robust and expeditious reinforcement of British forces in the Middle East,” helping influence Roosevelt’s decision to support Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa.

While historians debate the effects of his reporting on the campaign, they also note a unique irony: Fellers’ overly pessimistic assessments of British capabilities may have ultimately helped the Allies. His reports, many of which decried the British as ill-supplied and ineffective, convinced Rommel to overextend his supply lines in a drive toward Alexandria — a move that contributed to his defeat when the good source went silent.

His anti-British reporting and Rommel’s stunning successes during that time also influenced the American decision to supply new Sherman tanks and supplies to the British before their victory at El Alamein. It also encouraged Roosevelt and his commanders to focus on defeating the Axis in Europe first, over Japan.

Fellers went on to serve with the Office of Strategic Services and later under Gen. Douglas MacArthur in the Pacific. After the war, he played a controversial role in protecting Emperor Hirohito from war crimes prosecution.

The Black Code disaster remains one of World War II’s most consequential intelligence failures — a reminder that accurate intelligence reports mean nothing if the enemy is reading over your shoulder. Even today, Russian and Ukrainian forces have learned this lesson the hard way as intel is shared via social media, mobile phones, and new technologies, giving enemy forces new ways to access intel.

Story Continues

Read the full article here