Thirty-one North Korean commandos slipped past American and South Korean sentries on Jan. 17, 1968, cutting through the DMZ fence on a mission to assassinate South Korean President Park Chung-hee. Four days later, disguised as South Korean soldiers and wearing civilian trench coats over their weapons, they reached a police checkpoint 100 meters from the Blue House in downtown Seoul.

When Jongro police chief Choi Gyushik grew suspicious and drew his pistol, the commandos opened fire. The resulting firefight and eight-day manhunt killed four American soldiers, 26 South Koreans and 29 of the 31 commandos.

The Cold War on the Korean Peninsula

Park Chung-hee seized power in a May 16, 1961, military coup. The former Japanese Imperial Army officer transformed South Korea’s economy through rapid industrialization, building highways, steel mills and shipyards while increasingly tying the nation to the U.S.

But Park ruled as an authoritarian dictator who suppressed opposition through the Korean Central Intelligence Agency and cracked down on suspected communists with mass arrests and torture.

At the height of his power, Park sent 50,000 South Korean troops to Vietnam, deployed two ROK divisions along the DMZ, and purged suspected leftists from universities. Kim Il Sung viewed Park as the main obstacle to Korean unification.

In July 1967, Kim selected 31 officers from elite Unit 124 to assassinate Park, believing his death would trigger political chaos and allow North Korea to overtake the whole peninsula.

A Violent Period Along the DMZ

The timing of the raid was intentional. In October 1966, Kim Il Sung announced U.S. forces would be “dispersed to the maximum everywhere.” With more than 485,000 American troops in Vietnam by 1967, North Korea calculated Washington could not retaliate against any incursions.

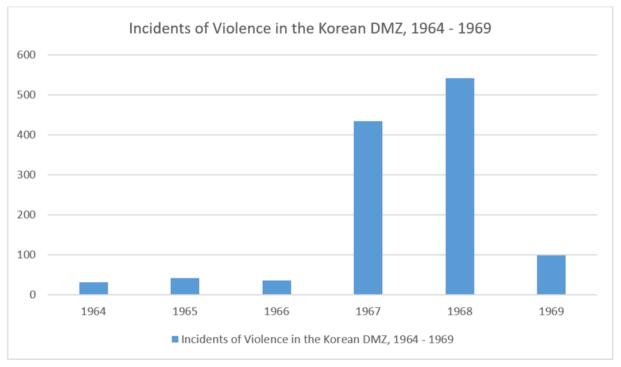

Between 1966 and 1969, North Korean forces launched hundreds of attacks against American and South Korean forces in the Korean DMZ Conflict. At the time, many people referred to it as the Second Korean War.

In the 2nd Infantry Division’s sector alone, 150 incidents including ambushes, firefights, and hostage situations occurred in 1967. Sixteen 2nd ID troops died and 51 were wounded in these engagements. The ROK Army sustained 115 killed and 243 wounded in the same sector.

In May 1967, North Korean operatives planted satchel charges inside a 2nd Infantry Division barracks at night, killing two Americans and wounding 16. The escalating violence prompted American commanders to reclassify northern South Korea as a hostile fire zone, making troops eligible for combat pay and the Combat Infantryman Badge.

By the end of the DMZ conflict, over 80 Americans would be dead, as well as over 200 South Korean soldiers.

Two Years of Training for One Mission

Unit 124’s all-officer commandos trained for two years. Their goal was to assault the South Korean presidential palace, known as the Blue House, kill Park, and spread chaos into Seoul.

They spent their final 15 days in training rehearsing on a full-scale Blue House mockup. Each commando carried 70 pounds of equipment including Soviet PPSh-43 submachine guns, pistols and grenades.

On Jan. 17 at 11 p.m., they cut holes in the DMZ fence in the 2nd Infantry Division’s sector. American sentries, more concerned with staying warm in sub-zero temperatures, failed to detect them. By 2 a.m. on Jan. 18, the commandos had set up camp in the hills 30 miles north of Seoul.

Four Brothers and a Failed Plan

On Jan. 19 at 2 p.m., four brothers from the Woo family were cutting firewood on Sambong Mountain when they stumbled across Unit 124’s camp. One brother noticed a commando’s rank insignia was sewn on upside down, meaning he was not a ROK soldier.

The commandos quickly detained the brothers and debated executing them. But the captain made a drastic decision, noting that digging graves in the frozen ground would be difficult, and some missing woodcutters might trigger searches by the authorities.

Instead, he ordered an hour-long lecture on communism’s virtues and made the brothers sign a document pledging silence. Then he released them.

The Woo brothers went directly to the police. Unit 124 broke camp immediately and raced toward Seoul, covering over 10 kilometers per hour. They reached Bibong Mountain by 7 a.m. on Jan. 20. Three South Korean Army battalions had searched for them but arrived too late and found no trace of the commandos. Authorities placed the capital on heightened alert.

The commandos entered Seoul in small cells on Jan. 20 before regrouping at Seungga-sa Temple. Realizing the increased security made their original plan impossible, they changed into ROK Army uniforms and marched openly through Seoul, posing as soldiers returning from patrol.

At 10 p.m. on Jan. 21, they approached a checkpoint 100 meters from the Blue House. Police chief Choi Gyushik noticed the group and stopped them for questioning. When they gave evasive answers, Choi noticed their coats and realized they were likely concealing weapons. He drew his pistol.

A commando shot Choi in the chest and killed him. Unit 124 opened fire with submachine guns and threw grenades at surrounding police. The Capital Garrison Command responded within minutes, even sending M48 Patton tanks.

After a quick but intense skirmish, the commandos scattered. A civilian bus accidentally drove into the crossfire. The commandos fired at it, killing several passengers.

Eight Days of Combat

President Park declared a state of emergency at 6 a.m. on Jan. 22, imposing curfews and mobilizing the reserves. The “Big Hunt” operation arrested over 1,000 suspected communist sympathizers within two weeks, detaining students, journalists and labor organizers.

The ROK Army’s 6th Corps deployed thousands of troops into the city. Some soldiers captured Kim Shin-jo on Jan. 22 after a homeowner reported a suspicious man near his property. Kim surrendered without firing his weapon.

American soldiers from the 2nd Infantry Division moved to block escape routes to the north. On Jan. 24, the 1st Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment encountered two commandos near the DMZ and opened fire. The Americans killed both commandos but lost one soldier killed and one wounded. Three other Americans were killed in similar close-range firefights against the commandos over the following days.

South Korean forces killed most of the remaining commandos over the next week. On Jan. 24, ROK soldiers killed 12 commandos near Seongu-ri. On Jan. 29, they killed six more, ending the manhunt.

Pak Jae-gyong was the only one to escape back to North Korea. Kim Shin-jo and another commando were captured, but the other commando committed suicide shortly after.

By the end of the manhunt, 26 South Koreans had been killed and 66 wounded, including 24 civilians. Four Americans were dead and several others wounded. Of the 31 commandos, 29 died or committed suicide.

The Raid Becomes an International Crisis

The raid occurred during an extraordinarily tense time. That same day, North Vietnamese forces began the Siege of Khe Sanh. Two days later, North Korea captured the USS Pueblo, taking 82 American sailors hostage. The Tet Offensive had erupted across South Vietnam.

President Johnson faced three crises within 10 days. With many of his troops bogged down in Vietnam and 83 Americans being held hostage, he declined to retaliate, fearing the start of WWIII or the execution of the hostages. He instead urged his cabinet to begin negotiations with Kim Il Sung.

The South Koreans felt that the North was actively invading and needed to be punished. Park was furious that the American refused to react. Johnson sent $100 million in military aid to placate Seoul.

Despite the aid package, the Korean Central Intelligence Agency went ahead and formed Unit 684. This group of 31 commandos was ordered to train and assassinate Kim Il Sung in a manner similar to the North Korean raid.

Unlike North Korea’s elite officers, South Korea recruited petty criminals and unemployed youths, promising them pardons, cash payments and government jobs. They failed to mention this mission was a one-way objective and there would be no extraction whether they succeeded or not.

The men trained on Silmido, an uninhabited island off Incheon measuring less than one square kilometer. For three years, they endured brutal training in hand-to-hand combat, knife fighting, parachuting and assassination techniques. ROK Air Force special forces instructors pushed recruits beyond their limits. Seven men died during this time.

By August 1971, inter-Korean relations had improved. Park, facing domestic political challenges, cancelled the mission. On Aug. 20, authorities told Unit 684 they would receive no pardons, payments or jobs. After three years of brutal training and death, they would simply be put back onto the streets.

On Aug. 23, 1971, Unit 684 mutinied. The 24 surviving recruits overpowered the guards, killing 18 personnel. They seized several weapons, escaped to the mainland, stole paratrooper uniforms, and hijacked a civilian bus near Incheon, planning to reach Seoul’s National Assembly to expose the illegal mission.

Military forces set up a roadblock in southwestern Seoul, forcing the bus to crash. After a brief standoff, several grenades detonated inside. Twenty mutineers died. Four survivors faced secret military tribunals. On March 10, 1972, all four were executed by firing squad. Their families were not notified. The government even refused to release the bodies.

South Korea concealed all information about Unit 684 for decades. Only in 2006 did authorities release an official report. In 2010, Seoul courts ordered the government to pay $231 million to families of 21 Unit 684 members, finding “the harshness of the training violated their basic human rights.”

Two Commandos, Two Different Fates

Kim Shin-jo underwent a year of KCIA interrogation. He was initially embittered by the failure of the mission and lamented the decision to spare the Woo brothers. He refused to be repatriated home.

During his imprisonment, he began receiving letters from Choi Jeong-hwa, a Christian woman. Her letters offered kind inspiration that was foreign to his indoctrination, including human dignity and forgiveness. He initially feared she was a sleeper agent or assassin sent by Pyongyang to tie up loose ends.

He was finally released in 1970 and immediately married Choi who inspired him to seek faith. He was baptized in 1981, confessing, “I came to kill the president, but God chose to save me.”

After becoming ordained as a pastor in 1997, he began helping North Korean defectors who escaped to the South. North Korean authorities murdered his parents in retaliation. Kim died in April 2025 at age 82.

Contrarily, Pak Jae-gyong became a hero in North Korea. The regime promoted him to brigadier general in 1985, major general by 1993, and four-star general by 1997. He became Vice Minister of the Ministry of People’s Armed Forces and served on state funeral committees for Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il.

In 2000 and 2007, North Korea sent Pak to Seoul as a diplomat to meet with the South Korean President. Pak is the only member of Unit 124 still alive.

President Park Chung-hee survived the 1968 raid only to be assassinated on Oct. 26, 1979, by Kim Jae-gyu, his own KCIA director, during a dinner at a KCIA safe house.

An Unfinished War

The Korean DMZ Conflict represented one small part of an unfinished war. By late 1969, Soviet pressure and international condemnation forced Pyongyang to scale back its attacks. Firefights dropped from 236 in 1968 to just 39 in 1969, while less than 100 confrontational incidents were reported across the entire DMZ that year.

But the provocations never fully stopped. Numerous incidents occurred throughout the rest of the century. Even in the modern era, North Korea continues to target South Korean forces and civilians.

In March 2010, a North Korean submarine torpedoed the corvette Cheonan, killing 46 sailors. In November 2010, North Korean artillery fired 170 shells at Yeonpyeong Island, killing two marines and two civilians in the first direct artillery bombardment of a South Korean civilian settlement since 1953.

In late 2015, North Korean soldiers place landmines near a South Korean guardhouse, maiming several soldiers. In January 2024, artillery fire near Yeonpyeong caused mass evacuations.

Approximately 100 U.S. servicemembers have been killed in hostile actions on the peninsula since 1953, including the four who died during the Blue House Raid and 31 Americans killed when North Korea shot down a Navy EC-121 reconnaissance aircraft in 1969. Over 450 South Koreans have died in these North Korean provocations.

No peace treaty has officially replaced the armistice as of 2025.

The 21st century has seen no American deaths from direct North Korean action, only because Pyongyang fears targeting U.S. forces. Nevertheless, American troops still guard the DMZ in a continued “conflict.” Approximately 28,500 U.S. servicemembers currently serve in South Korea.

Going into the 21st Century with the peninsula still technically in a state of war and recognizing that American and South Korean troops have been killed by direct North Korean attacks, Congress created the Korean Defense Service Medal in 2002.

The medal was created specifically because of incidents like the Blue House Raid, which shows that U.S. forces in Korea face constant danger. While the region is lower-level than active combat zones such as Syria and Iraq, the KDSM is designated as a campaign medal, qualifying recipients for both VFW and American Legion membership.

A crooked pine tree behind the Blue House still shows bullet holes from the Jan. 21, 1968, firefight. Officials preserved the tree as a memorial, leaving the damage visible as a reminder that North Korean forces are a constant danger to American and South Korean soldiers.

Story Continues

Read the full article here