Sgt. Kenneth Nine was scheduled to ship back to the states that Monday morning. After partying until 5 a.m. on Dec. 7, 1941, the 27th Infantry platoon sergeant sat exhausted in front of Schofield Barracks.

Then Japanese planes flew overhead, strafing everything in sight.

Nine’s commanding officer ran up and said, “Get in the saddle because you aren’t going anywhere.”

The 25th Infantry Division—just 67 days old—had entered World War II.

The division had been activated on Oct. 1, 1941, when the War Department reorganized the old Hawaiian Division, splitting it into two separate divisions: the 24th and the 25th Infantry Divisions.

This newly organized unit soon became one of the war’s most aggressive fighting forces. It was one of only two Army divisions to experience combat from that first chaotic morning at Pearl Harbor straight through to occupying defeated Japan almost four years later. Today, the division remains headquartered at Schofield Barracks, the same Hawaiian post where its World War II saga began.

Pearl Harbor: Baptism Under Fire

The division’s soldiers scrambled into action that December morning. Sgt. Nine ignored his hangover to break down supply room doors and get machine guns and ammunition onto the barracks’ rooftop.

Cpl. Bronsil Metz watched Capt. Dailey sprint across the parade ground, firing his .45 pistol at aircraft with zero chance of hitting them but every intention of fighting back. One officer exited his residence in his pajamas, firing his personal pistol at the incoming planes. Soldiers on the parade deck fired their Springfield rifles. One man accidentally dropped his Browning Automatic Rifle in the commotion, which discharged and wounded him.

Soldiers watched as Japanese planes swooped in, their machine guns ripping into the barracks walls and the parade deck. In the chaos, Private Walter R. French was killed, becoming the first man of the division to die in the war.

Soldiers fired back with whatever they had—rifles, pistols, even a hastily assembled machine gun that allegedly managed to down at least one enemy aircraft. When it was over, two men from the division were dead and 17 were wounded.

The two-month-old division immediately deployed to defensive positions along Oahu’s beaches. For the next year, soldiers dug fortifications, strung barbed wire, and trained obsessively in jungle warfare while watching for a potential enemy invasion. Sgt. Nine would remain with the division throughout the war.

In May 1942, Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins took command. An infantry officer who had missed World War I combat, Collins brought aggressive tactical instincts that would soon earn him the nickname “Lightning Joe.”

Meanwhile, the division needed a third infantry regiment before it moved to Guadalcanal. The 161st had been en route to the Philippines when Pearl Harbor was attacked and diverted to Hawaii. These Washingtonian National Guardsmen would fight alongside the regular Army’s 27th and 35th Infantry Regiments through the rest of the war.

The Battle for Guadalcanal

Having been one of the first divisions to see WWII combat, the division also had the distinction of being one of the few to launch the first offensive against Japan. The first elements of the 25th Division landed near Guadalcanal’s Tenaru River on Dec. 17, 1942, relieving the exhausted Marines.

Among them was Cpl. James Jones, a 21-year-old private in F Company, 27th Infantry, who would later immortalize the division’s experiences in his novels.

The soldiers faced a nightmare landscape of impenetrable jungle, inadequate maps, tropical diseases, and an enemy determined to die rather than surrender.

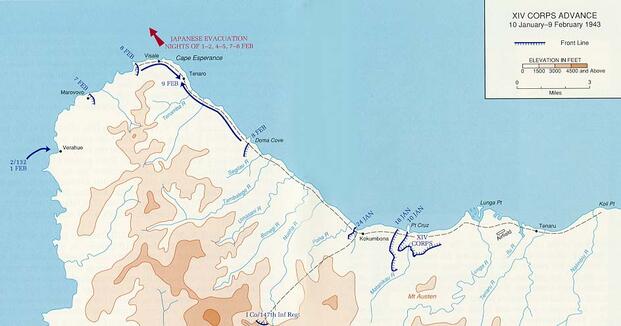

Collins received orders in early January 1943 from XIV Corps commander Maj. Gen. Alexander Patch to seize three objectives near the Matanikau River—Mount Austen, the Galloping Horse, and the Sea Horse.

The 27th Infantry Regiment faced the Galloping Horse, a 900-foot ridge that resembled a running horse. The 35th Infantry would tackle the Sea Horse while dealing with the Gifu strongpoint, a seemingly impregnable Japanese position on Mount Austen.

On Jan. 10, the attack began. The 35th Infantry’s assault on the Sea Horse turned disastrous when Company K walked into a massive ambush. Japanese machine guns shredded the advancing Americans.

As the company fell back, Sgt. William Fournier and Tech. 5th Grade Lewis Hall rushed to an abandoned machine gun. With another soldier holding up the weapon by its tripod to increase its field of fire, they turned the gun on advancing Japanese infantry. Both men received mortal wounds, but their actions earned posthumous Medals of Honor and saved Company K from complete annihilation.

The 27th Infantry hit snags in its move on the Galloping Horse, but kept pushing against the enemy. By Jan. 12, the regiment held Hills 51 and 52 but needed Hill 53—the horse’s head—to complete the objective. Water had run out. Men licked moisture from leaves; many were close to heat exhaustion.

Capt. Charles Davis, executive officer of the 2nd Battalion, volunteered to carry instructions to the companies caught in crossfire from Japanese machine guns. The Alabama native and University of Alabama law student navigated 800 yards of sniper-infested terrain, dodging bullets to reach Company E pinned down on a ridge.

Davis found the trapped soldiers, pinned by a Japanese machine gun nest blocking the advance. Grabbing several rifles and pistols, Davis led a direct assault on the position, killing its crew. Company E swept up the ridge.

Minutes after Davis’s assault, heavy rain broke the drought. Soldiers tilted their helmets or held them out to catch water. It was a welcome moment as they prepared for the final push.

Col. William McCulloch ordered his three artillery battalions to pound Hill 53. On Jan. 13, coordinated assaults from two directions swept through the weakened Japanese defenders. By the end of the day, the entire Galloping Horse belonged to the 27th Infantry.

Davis later received the Medal of Honor for his actions. Years afterward, attending Command and General Staff College, he sat in for an exam on infantry tactics. One question described an assault on an enemy position.

“The action described in the test was the same one I fought through on Guadalcanal,” Davis said later, noting the irony.

Meanwhile, the 161st Infantry cleared the Matanikau River Pocket, a dense jungle redoubt between a steep hillside and a cliff holding an estimated 500 Japanese troops. The combination of frequent assaults, heavy artillery bombardment, and starvation eventually eliminated this strongpoint.

The division’s 31-day Guadalcanal campaign ended Feb. 5, 1943, when elements linked with the Americal Division near Cape Esperance. The speed and aggression displayed by Collins’s troops was praised, though his division suffered several hundred casualties.

Lightning Strikes the Solomons

After five months garrisoning Guadalcanal, the division jumped back into combat in July 1943, landing on New Georgia to capture Munda airfield.

Col. James Dalton commanded the 161st, a West Point graduate who would become legendary for his leadership. The regiment moved for nine brutal days just to reach their attack positions against fierce resistance and monsoon weather. On July 22, after finally linking with other American forces at Bairoko, Dalton reportedly greeted the commander with an enthusiastic, “Boy, am I glad to see you!”

The 27th Infantry executed an impressive but harsh 19-day march through jungle mud to capture Bairoko Harbor. Soldiers slogged through waist-deep swamps, hacked through vegetation, and fought off nighttime infiltration attempts while advancing inch by bloody inch toward their objective.

The division cleared Arundel Island on Sept. 24 and seized Kolombangara with its vital Vila Airport on Oct. 6. Organized resistance on New Georgia ended on Aug. 25.

After almost a year in tropical combat zones, the division sailed for New Zealand in December 1943 for rest and training. The last elements arrived Dec. 5, exhausted but victorious. Following months of recuperation and replacement, the division moved to New Caledonia in February 1944 for intensive amphibious training in preparation for the American return to the Philippines.

The Liberation of the Philippines

The division landed at Lingayen Gulf on Luzon on Jan. 11, 1945. Maj. Gen. Charles Mullins Jr. had replaced Collins when he transferred to Europe to command VII Corps in the Normandy invasion. Soldiers were rested, re-equipped, and ready. They immediately drove across the Luzon Central Plain toward Binalonan, meeting Japanese forces there on Jan. 17.

The 161st Infantry Regiment encountered heavy resistance, turning back Japanese tanks and infantry to secure Binalonan the following day. The men discovered that the bulk of Japan’s 2nd Tank Division had dug in its tanks, converting them into stationary pillboxes in a desperate last stand.

Brig. Gen. Dalton, now the division’s assistant commander, personally led forces into the savage five-day Battle of San Manuel, where every building was a fortress and the tanks served as hardened bunkers. On Jan. 28, the 161st captured San Manuel after brutal house-to-house urban combat.

During the fighting, Tech. 4th Grade Laverne Parrish, a medic with the 161st Infantry, earned a Medal of Honor for repeatedly exposing himself to enemy fire to rescue wounded men. In the early hours of Jan. 24, when his company withdrew under intense fire, Parrish spotted two wounded men still in the field and crawled forward under enemy fire to bring both to safety in two successive trips. He was killed by enemy fire while evacuating additional casualties.

Moving through the rice paddies, the division occupied Umingan, Lupao, and San Jose, destroying Japanese armor with infantry assault weapons. Near Lupao on Feb. 7, Master Sgt. Charles L. McGaha of Company G, 35th Infantry, earned a Medal of Honor. When his platoon was pinned down by five Japanese tanks supported by ten machine guns and riflemen, he crossed 40 yards of open ground under heavy fire to move a wounded man to safety.

Despite suffering a severe arm wound, he returned to his post, assumed command when the platoon leader was wounded, and faced enemy fire multiple times to aid wounded soldiers. By the campaign’s end, the 25th had knocked out more than 250 Japanese tanks—a staggering toll achieved mostly by infantrymen using bazookas, rifle grenades, and satchel charges in close combat, while killing more than 6,500 enemy soldiers.

On Feb. 21, the division began operations in the Caraballo Mountains along Highway 5. The terrain featured steep ridges, thick jungle, and well-prepared Japanese defensive positions commanded by Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita himself.

The division pushed forward against fierce counterattacks, taking Digdig, Putlan, and Kapintalan. The fight for Balete Pass became a months-long battle of attrition. Japanese forces used the mountainous terrain brilliantly, creating layered defenses that blunted American firepower and mobility.

While serving as a platoon guide with Co. B, 27th Infantry, Staff Sgt. Raymond H. Cooley led an assault against several concealed enemy positions. When machine guns pinned his platoon down, Cooley advanced to one of the weapons and lobbed a grenade. The enemy threw it back as he armed and tossed another; the blast did not injure him.

After destroying the first gun, he charged another one, throwing more grenades into enemy positions along the way. As he armed another grenade, several Japanese troops charged him just as his men advanced behind him to meet them. To avoid hurting his own men in the blast, he dropped onto the grenade to shield them. He was severely wounded by the explosion, but his men managed to save him and destroy the last enemy position, earning Cooley a Medal of Honor for his heroic deeds.

On May 16, 1945, tragedy hit the division hard. Brig. Gen. Dalton, the day after his forces captured Balete Pass, was shot in the head by a Japanese sniper while inspecting the conquered defenses. In a letter sent weeks earlier to a friend, Dalton had written, “It goes okay out here, Pete, like any other corner of the war men live hard and scramble and scratch to beat the other guy — and some don’t come back.”

Dalton was one of only 11 U.S. general officers killed in action during World War II. The Filipino government later renamed the pass in his honor—it’s still called Dalton Pass today.

The capture of Santa Fe on May 27 opened the gateway to the Cagayan Valley. The division continued mopping up operations until June 30, having suffered approximately 650 killed and 1,920 wounded during the mountain campaign—the highest combat death toll of any division in the Sixth Army during the Luzon campaign.

Operation Downfall: The Invasion of Mainland Japan

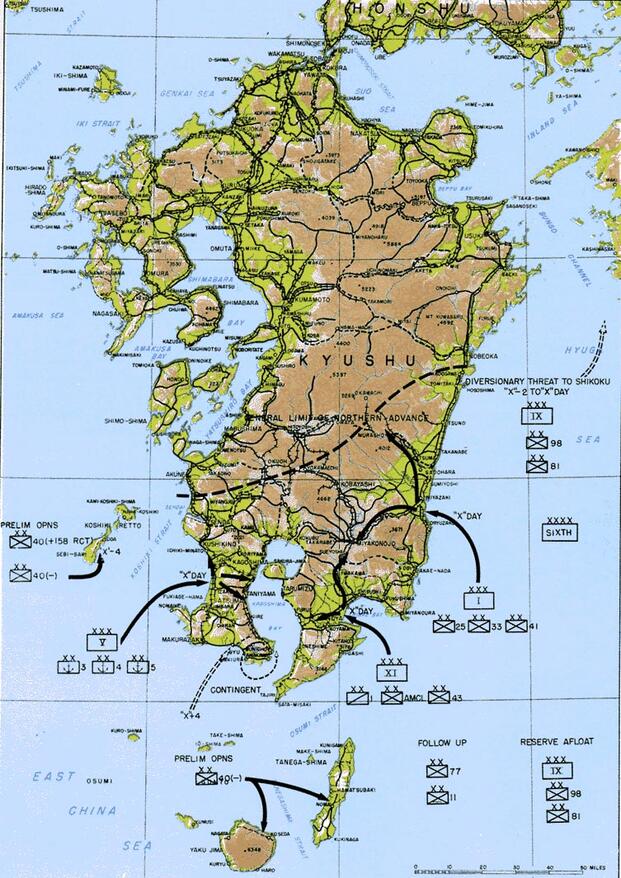

On July 1, the division moved to Tarlac for training, preparing for Operation Downfall—the planned invasion of Japan. The 25th was assigned to I Corps of General Walter Krueger’s Sixth Army for Operation Olympic, scheduled for Nov. 1, 1945.

The division would form part of the Eastern Assault Force, landing at Cord Beach south of the Oyodo River near Miyazaki on the eastern coast of Kyushu. Their objective was to capture Miyazaki city and its nearby airfield, then drive westward toward Miyakonojo to link up with the 43rd Infantry Division.

The soldiers knew what awaited them. Military planners estimated between 200,000 to 500,000 American casualties just for Kyushu, with potentially a million total to conquer all of Japan. The Japanese had assembled 700,000 defenders on Kyushu alone, with thousands of kamikaze aircraft waiting to strike the invasion fleet.

The atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as well as the Soviet entry into the Pacific War in August eliminated that grim necessity.

From Enemies to Allies

Instead, the division departed for Japan on Sept. 20, 1945, arriving to serve as occupation forces. They established headquarters in Nagoya on Honshu’s main island, later moving to Osaka in January 1946 to expand their occupation area.

On Nov. 1, 1945, the 161st Infantry was inactivated and replaced by the 4th Infantry Regiment. What followed represented an unexpected moment in the unit’s history. Soldiers who had fought viciously against Japanese forces across the Pacific now helped rebuild the shattered nation.

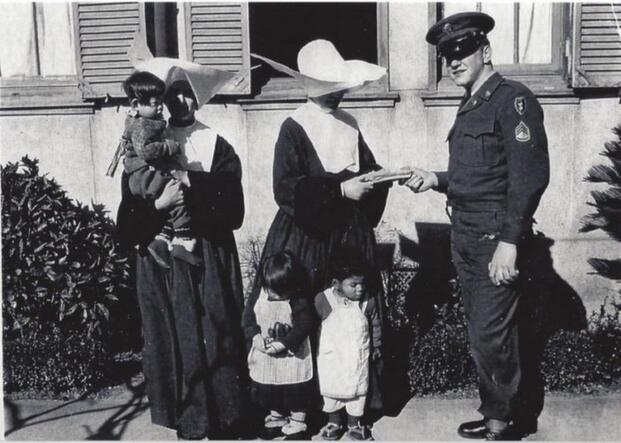

The local Holy Family orphanage in Osaka faced severe struggles in 1949, with many of the children being war orphans who lost their parents in combat or American bombings. Men from the 27th Infantry Regiment and 8th Field Artillery provided thousands of dollars in donations over the years.

They eventually adopted the orphanage to help care for the children, receiving worldwide recognition for their generosity. The relationship continues today—the regiment has hosted children from the orphanage for visits to Hawaii every year since 1957, a 75-year tradition that the soldiers proudly maintain.

Most Japanese civilians responded with amazement and gratitude to the kindness displayed by American troops. When a serious typhus epidemic hit Osaka, the 4th Infantry Regiment deployed 300 teams to work with Japanese authorities, helping eliminate the disease using DDT and inoculations.

The division remained in Japan until July 1950—nearly five years helping transform former enemies into democratic allies. But the occupation ended abruptly when North Korea invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950. The division deployed to Korea from its bases in Japan, beginning another chapter in its storied history. The soldiers poured thousands of dollars from their last paychecks in-country to the orphanage as they shipped out.

The Tropic Lightning Legacy

The 25th Infantry Division participated in four World War II campaigns: Central Pacific, Guadalcanal, Northern Solomons, and Luzon. Six soldiers earned the Medal of Honor for actions during the war. It had fought for 165 continuous days in combat, suffering roughly 5,423 casualties during the war.

In 1953, it adopted the nickname “Tropic Lightening” for its fast, aggressive fights from Hawaii, across the entire Pacific, to mainland Japan itself.

James Jones’s novels brought lasting literary fame to the division. “The Thin Red Line” became required reading for understanding Pacific War combat before the work was adapted to film in 1964 and famously in 1998. Jones’s earlier work, “From Here to Eternity,” captured the pre-war Army life at Schofield Barracks and earned both critical acclaim and a 1953 Academy Award-winning film adaptation.

From that chaotic morning at Schofield Barracks to occupation duty in Osaka, the brand-new division earned its place as one of the most storied units in the U.S. Army. The lightning bolt superimposed on a Taro leaf remains one of the Army’s most recognizable shoulder patches.

While soldiers jokingly call it the “Electric Strawberry,” the patch honors the division’s Hawaiian roots and its WWII experiences. Only the 25th and its sister division, the 24th, can claim they were the first to fight against the Japanese during the war and occupy the enemy nation years later.

Story Continues

Read the full article here