Sometimes humanity has to relearn old lessons. Nationwide, property taxes have spiked over the last five years – why? With overall taxes already high, plus high debt, debt service, and projected debt, how can State policymakers – everywhere – reduce the property tax burden on citizens?

Let’s start with the basics. Nationally, the average property tax bill has increased 20 percent in five years—from $2,340 to $2,795—while the “effective property tax rate” dropped only a fraction.

Okay, stop: What does that really mean? It means overall home valuations (what local assessors say your home is worth) jumped up, while state offsets, such as relief for seniors on fixed incomes, veterans, and the famous “homestead exemption” (a percentage of your home’s value), did not jump – in some states, like Maine, got rolled back.

Okay, stop again: How did this happen? After COVID in 2020, several things unfolded nationwide. Mandates came down, businesses failed, and supply chains got gummed up. A bottleneck in housing stock developed, too few homes for buyers. Fewer were built, by fewer builders.

That was not all. A shortage of homes meant – since prices reflect demand – prices rose, with a ripple effect. If you sold your home at a higher value, you had to buy or rent one at a higher cost.

Beyond this, home prices spiked because government spending exploded—state and federal. You may ask how this could affect home prices, but it is really simple. Deficits skyrocketed—that is, the difference between what the government collects and spends. To cover the gap, government leaders borrowed more money, and the feds printed more, cheapening the dollar, so things cost more.

So, on top of too little housing stock, which meant more people competing for houses to buy and rent, we also got higher costs generally, which figured into the cost of buying and renting houses. If you want to see how things snowball, economists think inflation comes down when you raise the price of borrowing money, that is interest rates on credit cards, cars, and houses, so they did that.

Now, back to higher property taxes. These mostly pay for schools. As costs climbed, so did the cost of building, maintaining, and commuting to schools, even before electric buses. This was doubly so in America’s more rural states, like Maine.

But that was not all. Beyond higher real estate prices, excess spending, inflation, and interest rates, property taxes jumped up for other reasons, related but slightly different. In states like Maine, the state pays a big chunk of school costs, so if they can shift that to locals, it helps their budget.

Traditionally, limits were set by the state on how high towns could assess home values, generally 80 percent of market value, maybe less. States also allowed exemptions for seniors long in their homes, many on fixed incomes, and helped veterans. Finally, they allowed the “homestead exemption,” which reduced property tax bills, helping local economies.

In Maine, which happens to have the highest property taxes in the nation – thanks to a Democrat legislature and governor – these homeowner-friendly provisions were largely rolled back. In effect, the state quietly pushed the higher costs for everything, especially schools, to the town and to you, reducing well-established means for keeping your tax burden lighter.

The kicker is this. In states from Maine to California, someone has to pay these high property taxes, and that’s you. You do that with your income. If income growth somehow kept pace with property tax growth, we would have air to breathe, but it has not. People feel crushed and pressed to stay in their homes.

Unfortunately, even as property taxes explode in Democrat-controlled states, no tax relief is in sight, and schools struggle with higher costs, lower enrollment, and more needy students – income lags.

Rather ironically, rural states like Maine are in a vice – high real estate values, lost tax exemptions, low housing stock, excess spending, stressed school budgets, kids in need, and low-income growth – all combining to crush average taxpayers.

So, what is the answer? Restore tax predictability, and keep tax rates and income growth in balance. How? Reverse engineer the failure. State budgets need to be in balance, spending unapologetically cut. Tax exemptions for seniors, veterans, and homeowners were restored, and school needs were met by ruthlessly accountable, long-term recapitalization programs, focused on outcomes, not inputs.

Finally, since everything is tied together, pro-growth policies like tax cuts, and not taking hikes, need to be prioritized for state revenue growth, businesses attracted not chased away, property taxes brought down, as good jobs are created, keeping kids in the state, skills up, housing affordable, prices lower.

In the end, high property taxes are just a symptom of something more serious, lack of focus on the well-being of the average citizen, what he or she can really afford, what they want, and rolling back government excesses. Sometimes humanity has to relearn old lessons. Looks like that time.

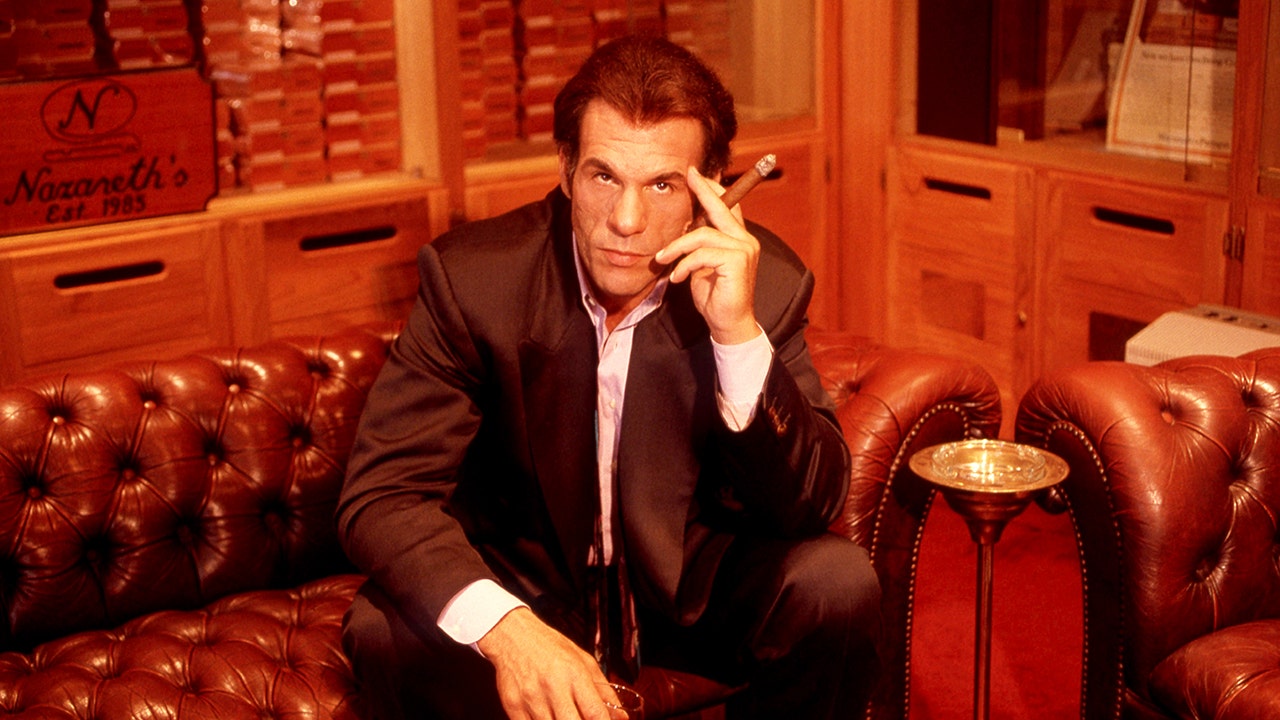

Robert Charles is a former Assistant Secretary of State under Colin Powell, former Reagan and Bush 41 White House staffer, attorney, and naval intelligence officer (USNR). He wrote “Narcotics and Terrorism” (2003), “Eagles and Evergreens” (2018), and is National Spokesman for AMAC.

Read the full article here