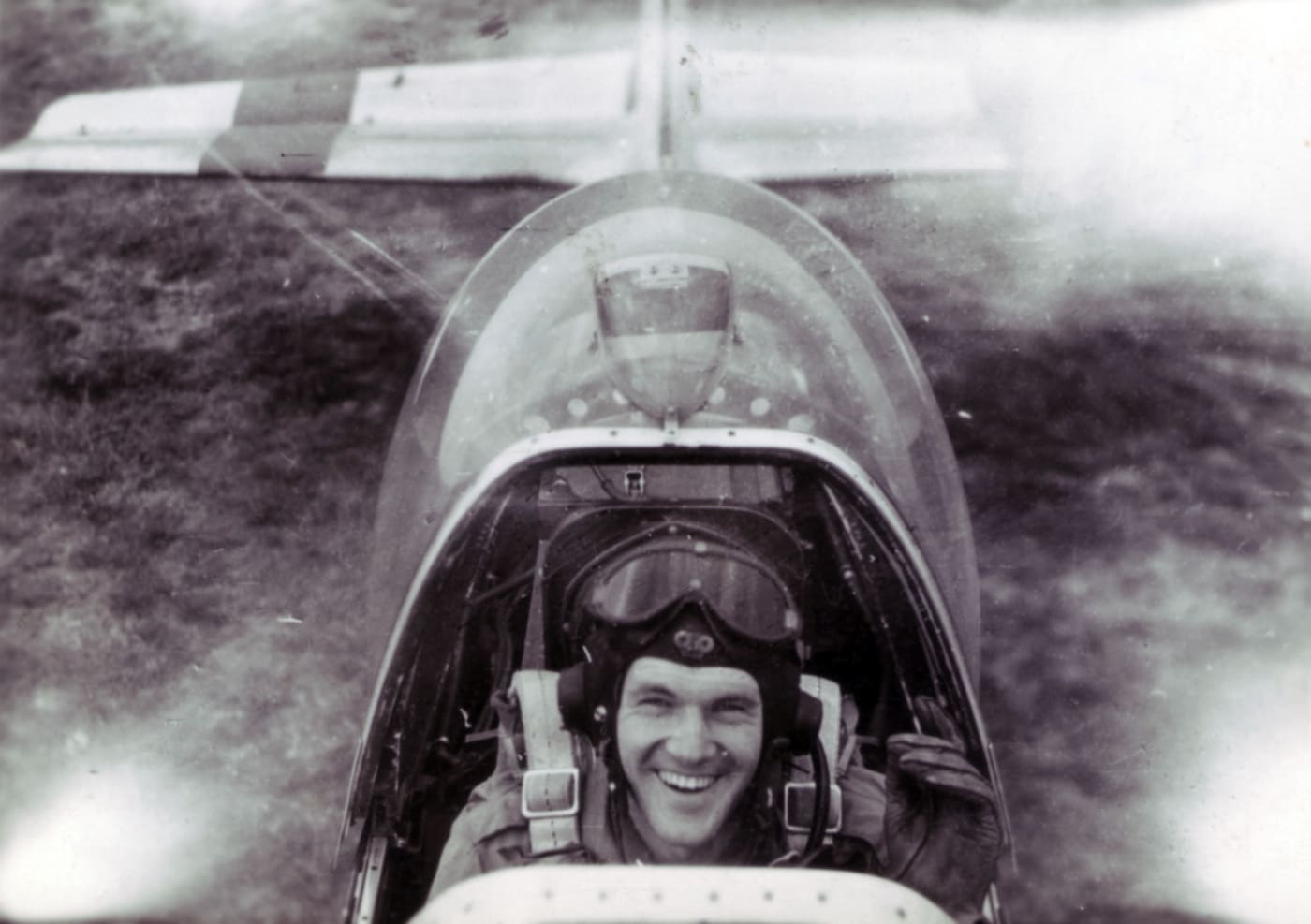

Elmer Pankratz is nearly 102 years old. He is one of America’s few remaining North American P-51 Mustang pilots from World War II. And he might very well be the last F-6D Mustang pilot, the camera-equipped photo recon variant of the North American fighter.

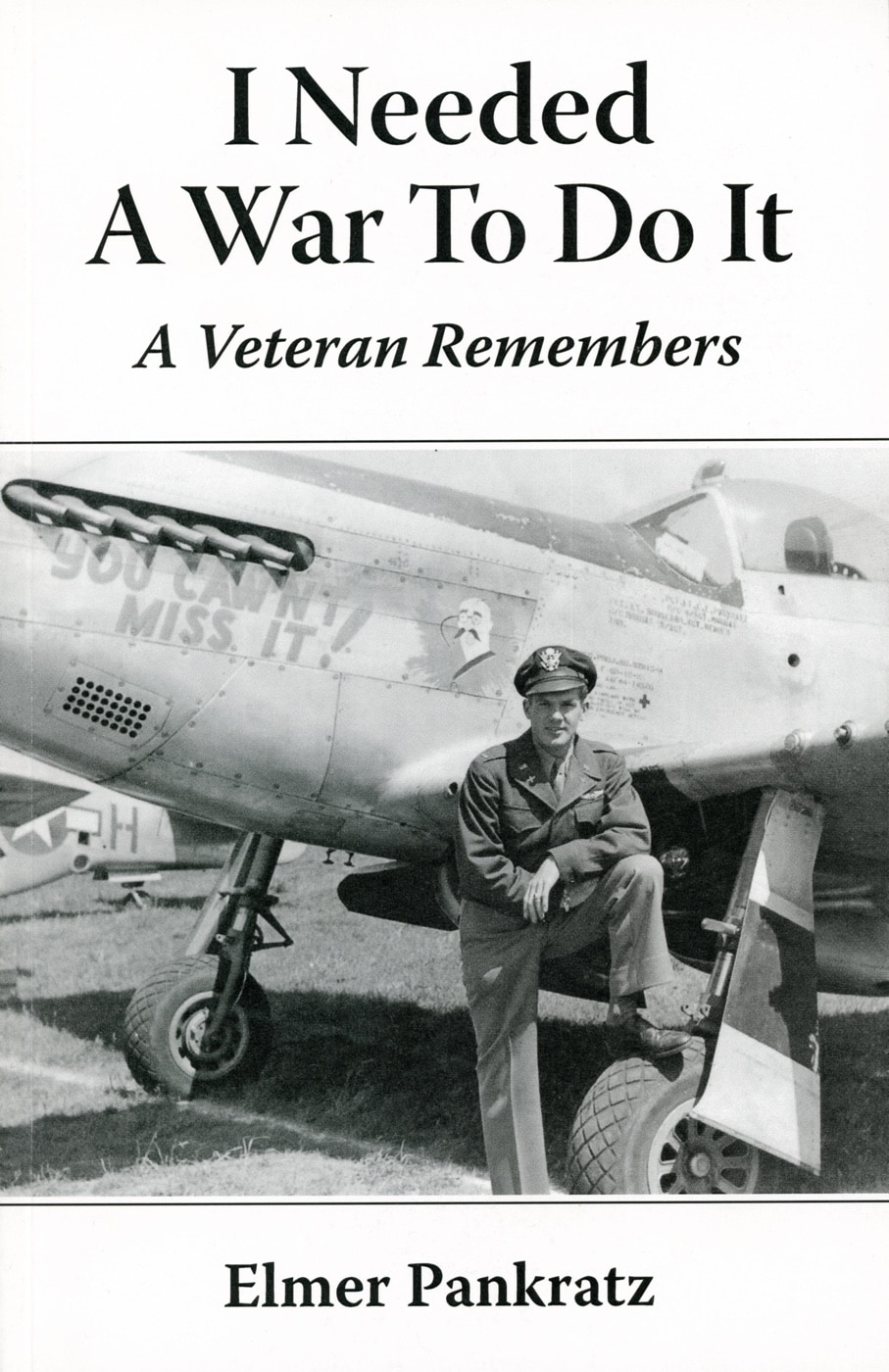

I met Elmer back in 2007, and working together we brought his wartime memoir “I Needed a War To Do It” to print. More than that, Elmer found himself in demand as a speaker at various aviation and veterans’ events. He’s gladly been able to personally share his story with a lot of folks and provide some background on not only what it meant to fly the P-51 Mustang, but also about the highly valuable but greatly overlooked job of a tactical reconnaissance pilot.

I had the opportunity to sit down with him recently and I thought The Armory Life readers would like to know about Elmer’s wartime experiences.

Dreams of Flying

Like many young Americans during the Great Depression, Elmer had great dreams, but there was little money available to realize them. College was not an option, at least financially, and after the Japanese attacks at Pearl Harbor, Elmer was waiting for Uncle Sam to call and “tell him where he was needed”. As far as he knew, the U.S. Army Air Corps required at least two years of college before a candidate could be considered for flight training.

That all changed when a friend from high school showed up with silver wings on his chest. The buddy had become a pilot, and the Air Corps had opened up the requirement to a high school diploma. With a diploma in hand, Elmer was quickly at the Air Corps recruiting station, and he was accepted for flight training.

Sadly, while Elmer was in Primary Training at Carlstrom Field (near Arcadia, Florida) he learned that his friend, Hank Rose, was missing in action. Hank had given him the encouraging news about the Air Corps’ new requirements, and as Elmer went into flight training Hank went into combat. A couple months later Elmer received a newspaper clipping from home noting that Hank had been killed on his first mission.

Harsh Lessons in Training

Long before the dangers of flying combat missions, the basics of flying at all proved dangerous enough. Piloting the Vultee BT-13 basic trainer from Courtland, Alabama, Elmer and his training class were tasked with completing a triangular-shaped, three-hour night flight — on a particularly dark evening, with no horizon showing. The cadets would have to rely on their instruments, a very difficult mode of flying. The young pilots had to focus on their instruments, read them correctly and trust in them, all while scanning for any possible waypoint to observe without being overcome by vertigo.

Elmer found himself in trouble: “I looked at a forest fire a little too long and when I checked my instruments, they told me that I was in a spiraling dive. My senses told me that I was NOT doing this, but that little voice in my head said, ‘trust your instruments…trust your instruments!’. The instruments were right, but after I got everything back on track, I had gone from fat-dumb-and-happy, to alone, uncertain, and scared. Then I heard pleading and panic on the radio and one voice said, ‘I’m bailing out’. The mind can do funny things to you, because I remember unbuckling my belt in preparation to go over the side. Then the sensible part of my brain took over, and said: ‘Hey dummy, look at your gas gauges, you have two hours of fuel left and you are still in control of the plane, so buckle up and find the damn field!’”

Elmer did find the airfield and landed safely. He was one of the lucky ones. A total of 35 planes went out that night, and 11 of them crashed in the darkness. Eight cadets died.

Elmer described the carnage he knew about: “One of the cadets got back, called in for landing instruction, and then crashed in the pattern. He probably relaxed and vertigo got him. One got back with tree branches stuck in his plane because he found what he thought was a lighted runway, made a landing pattern on it, and at the last instant realized that it was an elongated forest fire. One Cadet stayed in the air until dawn’s earliest light, and landed on a highway. Field personnel said it was not possible to keep a BT in the air that long, but he did. One guy somehow found an open farm field and did a good job of getting his plane on the ground, only to hit the one tree in the middle of the field.”

There was no time to mourn. “The excitement of going to single-engine Advanced Flying School dulled the shock of my last days at Courtland Field. I found that my best defense against tragedy was to get right back into action, and it seems that in a short time I was too busy to think about it. This may sound cold and uncaring, but that is not so. Any other reaction would have finished my flying. Now 80 years later, I still feel a very heavy sadness. It is not with me constantly, but it never goes away.”

A Close Call for Elmer Pankratz

The dangers of training continued. After several rain delays at Fort Myers, Florida, Elmer was ready for his first solo flight in a fighter, the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk. He told me that he was totally out of character that day, incredibly nervous and with his knees shaking so badly he thought he would knock out the cockpit walls. All these years later, his mind is clear about the mistake he almost made that would have cost him his life, and he is quick to remind us that the devil is in the details.

Elmer’s P-40 was third in line for takeoff. The Warhawk’s big Allison V12 liquid-cooled engine (1,240 hp) was notorious for overheating, and the temperature on the Florida airfield was high. As Elmer idled at low power waiting his turn, he noticed that his oil temperature gauge was climbing into the red.

At that moment, the pilot in the first slot reported that his engine was overheating and asked the tower for instructions. The answer came back for all the aircraft to shut their engines down. As a tractor was towing his aircraft back, Elmer noticed that he had set his trim tab in the LEFT position — the exact opposite of where it needed to be. The torque of the P-40 required that the trim tab be set to the RIGHT to keep the aircraft straight when on full power for takeoff.

What would have happened if he tried to take off with the trim set incorrectly? “I would have swerved, crashed and died on my first takeoff in a fighter”, Elmer said flatly. Instead, he walked away unscathed. The next day, he received a 10-day pass. When he returned, he soloed in a P-40 without a hint of nerves. He had become a fighter pilot.

My Kingdom for a Mustang

By June 23, 1944, Elmer had 88 hours flying time in the P-40, and it was time for him to pay his dues. “The big questions were, where am I going, and what will I be flying?” he thought. “Most likely it will not be the P-40 because, as fine an airplane as it is, it is obsolete. So, it will probably be the P-47 Thunderbolt or the P-51 Mustang. My dream airplane was, and always will be the beautiful North American P-51.”

A notice on the bulletin board stated that volunteers were needed for Tactical Reconnaissance. No one knew what that was, until one guy said, “You do aerial spying, and you only fly in pairs, and the Germans don’t like it, so they really go after you. So, stay away from it.” It sounded like good advice to Elmer, so he ignored the notice.

Apparently, most all the other pilots did the same, because a few days later another notice was posted, stating that volunteers were still needed and that anyone who volunteered would be flying Mustangs, and receive an immediate, extra 10-day leave. “That meant 10 more days at home, and I would be flying my dream airplane. So, what’s to think about!?! Sign me up now and I will worry about the dangerous stuff later!”, Elmer said.

Elmer was sent to Key Field near Meridian, Mississippi on June 23, 1944, for training in tactical reconnaissance. He describes it as “aerial cavalry”, with fast horses roaming behind enemy lines equipped with cameras to discover and photograph their operations.

“Our Mustangs were armed, and we practiced gunnery, but over and over it was impressed upon us that our mission was getting information, and to use our guns only if we were attacked. Getting my hands on the Mustang would have to wait, because the early training was in the trusty P-40. At Page Field, the emphasis was on aerobatics and formation flying, but at Key Field, the emphasis was on low-level navigation and using the cameras. One of my first missions was to photograph a specific bridge over a river. It gave me a boost of confidence when I found the bridge and got good pictures of it. I also found out how hot a fighter gets on the deck in the summer in Mississippi. There was no air conditioning in those babies!”

Elmer’s first Mustang flight did not leave him disappointed: “The big day came. I do not remember any excessive nervousness on my first flight in the Mustang, and she came up to all my expectations. The Rolls Royce Merlin engine has a distinctive sound on take-off, which I can only describe as a very high decibel snarl.

“The power surge was the most I had experienced, and it really had my full attention. I was cautioned to advance the throttle slowly, and not wallop it to the stop as I had in every other plane I flew so far. The power connected to that big four-bladed propeller created unbelievable torque, which could easily make a new Mustang pilot lose control and swerve off the runway. Even worse, there were reports that P-51s had flipped — not a good thing to do. I did everything right, so I was quickly airborne, and then I marveled at the lively response to the controls. There was no horsing this thoroughbred around the sky; just ask her and she would do it. What a joy to fly!”

Elmer notes that there is an important distinction in his Mustang mount, because he flew the photo-recon variant that was officially called the “F-6”:

“The Mustangs I was flying were called F-6’s. This meant they were fully armed P-51s with two large cameras mounted inside. One took pictures at a 45-degree angle down from the left side of my plane, and the other camera was mounted on the bottom near the tail and took pictures directly below. The negative size was 10″x 10″, and the prints were the same size and were very sharp.

“I did not have a sight that I could place on the target, so I had to develop a talent for judging where my cameras were pointing — it was more art than science. I was always anxious to see my pictures after a mission and was usually pleased to see that they came out okay. Even so, I was getting itchy to finish training and get into real action. On November 6, 1944, 19 of us received orders stating that we were assigned to ‘Shipment FK 555 DJ’. We were to immediately proceed by rail to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, for dispatch overseas through the NYC Port of Embarkation. I was on my way.”

Welcome to the Battle of the Bulge

Elmer’s introduction to combat came during the Germans’ surprise offensive in Belgium during December 1944, known as the “Battle of the Bulge.” It was a rude awakening for a pilot hoping to get into the seat of Mustang for his first combat mission.

“I was in the replacement Depot in Paris only long enough to get processed through to Brussels, Belgium. With another pilot, we were told to get to field Y-10 and report to Major McNabb, the CO of the 160th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron. When we asked where Y-10 was, we were told that the train crew would know. It didn’t take long to find that we had a problem — because the train crew only spoke French, and we didn’t. I have no idea where the train went, but as dawn approached, we were back in Brussels. We went back to the replacement depot and told our story.

“That night, we were on another train and were assured that the crew knew where to drop us off. Sure enough, they dropped us off at a flying field, except it was a P-47 fighter field, the wrong one. At least the Thunderbolt men knew where Y-10 was, so they piled us in a Jeep and it looked like we might just finally get to our field. It was my first Jeep ride and, as great a vehicle as it is, it is a real boneshaker. Suddenly, our driver slammed on the brakes, and miraculously none of us were ejected. We had been challenged by MPs, and if we had not stopped, their next action would have been to shoot to kill.

“That is how I was introduced to the Battle of the Bulge. We learned that the Germans were roaming around in Jeeps while dressed in American uniforms, with the intent to create maximum confusion. It was about 11:00 PM by the time I finally reported in, and when I was shown where my sack was, it turned out to be a wood-framed Army cot, complete with canvas “mattress”. I was so tired even that felt good, but at about 3:00am, I was rousted out of the sack and told we were being evacuated to France because our field was threatened by the German advance!”

Between avoiding rampaging Germans and dealing with a lack of recon aircraft, Elmer stayed on the ground for nearly a month. His first mission came on January 15, 1945, with a trip to Kaiserlautern. He’s never been afraid to admit his fears, and he always seemed to find a way to quickly overcome them. “I was very nervous on my first few missions, because no matter where I looked, I just knew that danger was threatening from a different direction. I was constantly jerking my head around to cover the sky. In time, I learned to cover the sky slowly, which was more effective and easier on my nerves, and my neck.”

The Mustang in Winter

His 160th Tactical Recon Squadron was based in France during the Battle of Bulge. By February 1st, the squadron moved back to Y-10 in Belgium. Y-10 was a rough-hewn forward field, and operating conditions were strained by the weather in the coldest winter in Europe in nearly 175 years. First came the heavy snow, then came the mud. Either way, it was always cold.

February was a busy month for Elmer and his squadron, but he also received a great gift: the 160th was equipped with the latest model Mustang, the “D” variant. The F-6D was his dream mount, and Elmer referred to North American’s fabulous fighter as his “aluminum sweetheart”.

“When the D model came out, the fuselage was modified so that a glass bubble covered the entire cockpit. This gave me the visibility of an open cockpit. The only downside was that on a sunny day, the greenhouse effect made things very hot, even in the winter. There was no air conditioning!”

On one mission in February, Elmer acted as a spotter for American long-range artillery. Near Julich, he called in the corrections on what appeared to be an unimportant speck on the map. After several adjustments, long-short-left-right, there was a massive explosion. Another successful mission, but he had no idea what was hit.

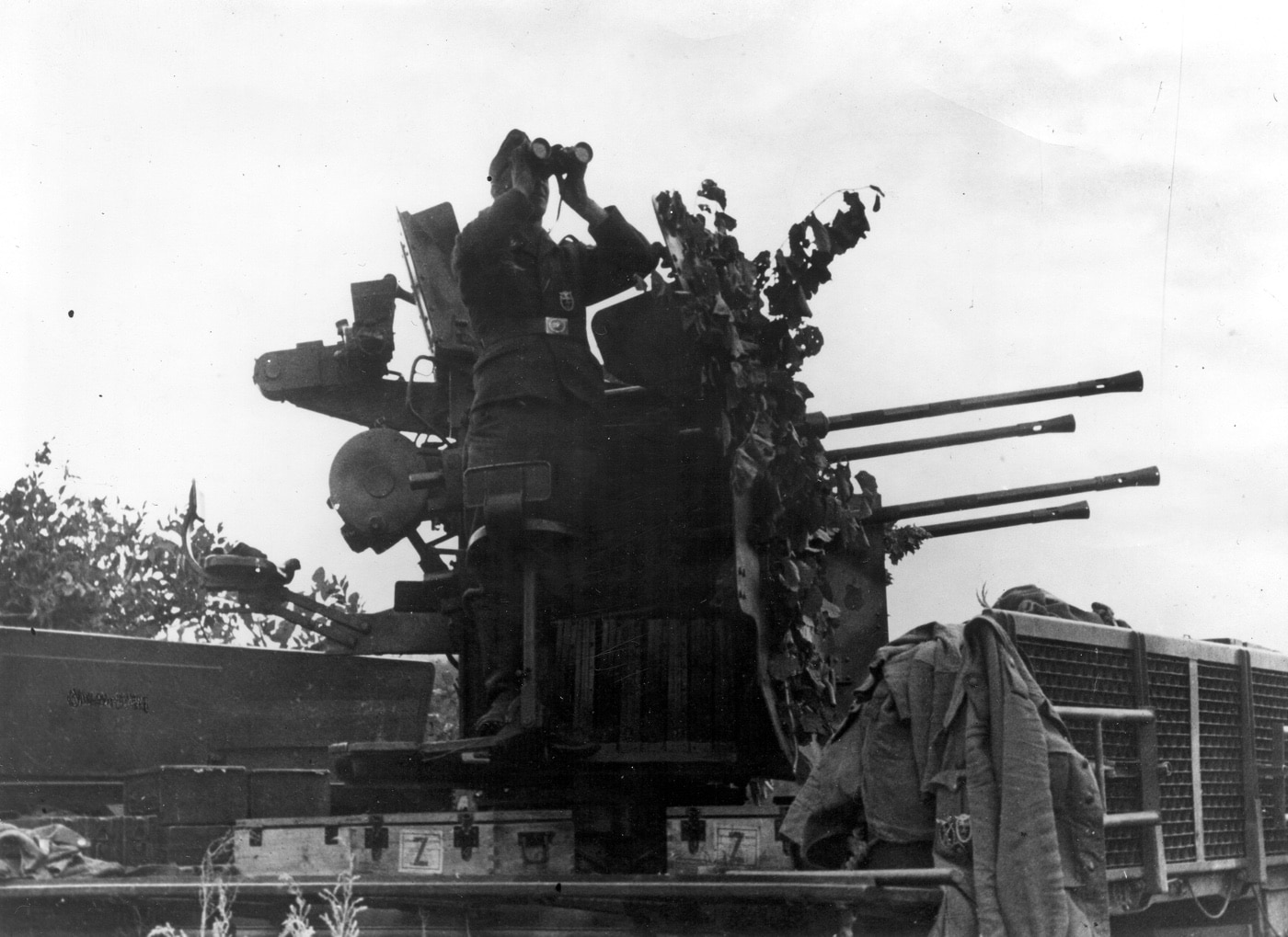

Fighting Through the Flak

Tactical recon missions could be uneventful — right up until the time they weren’t. With the power of the Luftwaffe fighter force on the wane, German flak was the prime enemy. Elmer was shot at many times, and even “boxed in” by the fire of an 88mm battery. Each time he made it back without a scratch — to himself or his Mustang. The “twinkling lights” of German flak never caught him.

“When we saw flak, we were all over the sky — climbing, diving, turning, until we were clear of the danger. We flew our missions at 6,000 feet. We were told the heavy flak was not as accurate at this height, and that the light flak was beginning to reach its maximum range — so that’s where our chances were best. In those days, I could see a dog running down a road from 6,000 feet. Today, I couldn’t see an elephant from up there. Ah, to have those young eyes again!”

He has plenty of stories from his 43 combat missions. One stays with him to this day, and it comes up almost every time we meet. On March 2, 1945, near Munster, Elmer spotted a train. By this point in the war, it was a particularly remarkable sight to find a high-value target traveling in daylight in Germany. The Luftwaffe had lost control of the air, and Allied fighter-bombers ranged all over the Reich. Consequently, German road, rail and barge traffic traveled by night.

Elmer radioed in the finding, and his Intel Officer kept him on station to help guide the P-47 Thunderbolts that had been dispatched to the scene. Soon enough, the Thunderbolts arrived, and they clobbered the train. However, there was a flak car in the mix, and the German AA crews hit one of the P-47s and the pilot bailed out.

Elmer says: “I saw a chute open, and the pilot landed in the middle of a big, open field. He was okay and ran for the closest woods. The trouble was that the woods were towards the destroyed train. If any of the train crew got him, he may not have lived to become a POW.”

He wonders about that Thunderbolt pilot to this day — another unresolved war story for a pilot trained to observe.

All the Way Home

When the war ended in Germany, Elmer stayed in country and was preparing to be sent to China to continue flying recon missions in the China-Burma-India theatre. In the meantime, he flew as often as he could. When the atomic bombs fell on Japan, there was nothing left to do but go home.

Nowadays he enjoys his life, and still lives in his own home. He gave up driving a few years ago, but his friends and family get him around, and his schedule is as busy as folks half his age. At his local American Legion Hall, the guys have started a fund to get Elmer back in the air in a P-51 Mustang (two-seater) when he turns 105. “Do you have any idea how ridiculously expensive that will be?!?”, Elmer asks them. They respond with: “You just focus on making it to 105.” I expect that he will.

“I Needed a War to Do It”

While Elmer’s fascinating book “I Needed A War To Do It” is now out of print, it provided a great description of his military career and his path to become a pilot:

“Almost three years had passed since Private Elmer Pankratz started his military career. He studied, sweated, agonized, and prayed his way through basic training and five flight schools. He earned his silver wings, became a Lieutenant, and went on to fly 43 combat missions in his dream airplane, the P-51 Mustang. He flew in the European Theatre in the Rhineland, the Ardennes, and the Central Europe campaigns. He was awarded the Air Medal with 6 Oak Leaf clusters, and the Belgian Fourragere. That is me, and it took a war for me to do it.”

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Read the full article here